This is the January 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the January 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on January 23.

Your opinion has been registered for the January 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on January 23.

A Review of the Facts

A public agency retains the services of VWX Architects and Engineers to perform a major scheduled overhaul of a bridge. VWX Architects and Engineers retains the services of Engineer Sam, a civil engineer, as its subconsultant to perform bridge inspection services on the bridge. Sam’s scope of work is solely to identify any pavement damage on the bridge and report the damage to VWX for further review and repair.

Three months prior to the beginning of the scheduled overhaul of the bridge, while traveling across the bridge, Police Officer B loses control of his patrol car. The vehicle crashed into the bridge wall. The wall failed to restrain the vehicle, which fell to the river below, killing Police Officer B.

While conducting the bridge inspection, and although not part of the scope of services for which he was retained, Sam notices an apparent pre-existing defective condition in the wall close to where the accident involving Police Officer B occurred. Sam surmises that the defective condition may have been a contributing factor in the wall failure and notes this in his engineering notes. Sam verbally reports this information to his client, which then verbally reports the information to the public agency. The public agency contacts VWX Architects and Engineers which then contacts Sam and asks Sam not to include this additional information in his final report since it was not part of his scope of work. Sam states that he will retain the information from his engineering notes but not include it in the final report, as requested. Sam does not report this information to any other public agency or authority.

What Do You Think?

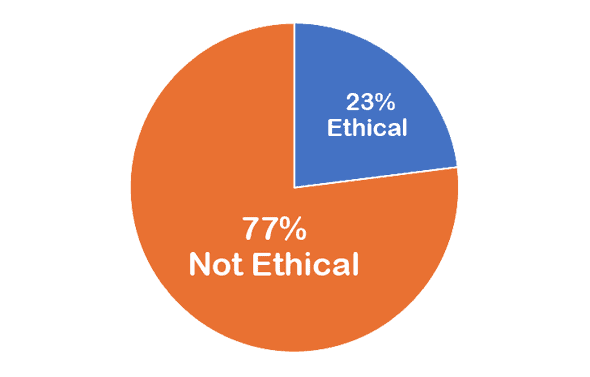

Was it ethical for Sam to retain the information in his engineering notes but not include it in the final report as requested and to not report this information to any other public agency or authority?

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

II.1.c

Engineers shall not reveal facts, data or information without the prior consent of the client or employer except as authorized or required by law or this Code.II.3.a

Engineers shall be objective and truthful in professional reports, statements or testimony. They shall include all relevant and pertinent information in such reports, statements or testimony, which should bear the date indicating when it was current.III.1.a

Engineers shall acknowledge their errors and shall not distort or alter the facts.III.2.b

Engineers shall not complete, sign or seal plans and/or specifications that are not in conformity with applicable engineering standards. If the client or employer insists on such unprofessional conduct, they shall notify the proper authorities and withdraw from further service on the project.

Discussion

Engineers play a vital role in society in providing a higher degree of assurance that the products, systems, facilities, and structures used by the public are safe and effective. Engineers are frequently placed in situations where they must balance the extent of their obligations to their employer or client with their obligations to protect the public health and safety.

An example of this basic ethical dichotomy was considered by the NSPE Board of Ethical Review in Case No. 89-7 (which the Board also applied in Case No. 97-5). In that case, an engineer, Engineer A, was retained to investigate the structural integrity of a 60-year-old occupied apartment building, which his client was planning to sell. Under the terms of the agreement with the client, the structural report written by Engineer A was to remain confidential. In addition, the client made clear to Engineer A that the building was being sold “as is” and that the client was not planning to take any remedial action to repair or renovate any system within the building prior to its sale. Engineer A performed several structural tests on the building and determined that the building was structurally sound. However, during the course of providing services, the client confided in Engineer A and informed him that the building contained deficiencies in the electrical and mechanical systems, which violated applicable codes and standards. While Engineer A is not an electrical or mechanical engineer, he does realize those deficiencies could cause injury to the occupants of the building and so informs the client. Specifically, in his report, Engineer A made a brief mention of his conversation with the client concerning the deficiencies; however, in view of the terms of the agreement, Engineer A did not report the safety violations to any third party.

In deciding it was unethical for Engineer A not to report the safety violations to the appropriate public authorities, the Board noted that the facts presented in the case raised a conflict between two basic ethical obligations of an engineer: The obligation of the engineer to be faithful to the client and not to disclose confidential information concerning the business affairs of a client without that client’s consent, and the obligation of the engineer to hold paramount the public health and safety.

As noted in Case No. 89-7, there are various rationales for the nondisclosure language contained in the NSPE Code. Engineers, in the performance of their professional services, act as “agents” or “trustees” to their clients. They are privy to a great deal of information and background concerning the business affairs of their client. The disclosure of confidential information could be quite detrimental to the interests of their client and, therefore, engineers as “agents” or “trustees” are expected to maintain the confidential nature of the information revealed to them in the course of rendering their professional services.

Turning to the facts in this case, it is the Board’s position that the facts and circumstances in Case No. 89-7, while somewhat similar in nature, are significantly different than the facts in the present case. First, it is clear that, unlike Case No. 89-7, which involved facts and circumstances that were openly conveyed directly to Engineer A from a client, in the present case, the circumstances bearing on the public safety were revealed to the engineer as part of the engineer’s inspection and professional observations. Presumably, the manner in which information is conveyed to an engineer will have some bearing on the client’s expectation of the engineer’s maintaining the confidentiality of the particular information. In the present case, it is difficult for this Board to conclude that the client or the public agency could have had a genuine expectation of confidentiality, since nothing of a confidential nature was directly conveyed by the client or the public agency to Sam.

Another difference between the two cases is that in Case No. 89-7, there was a specific agreement between the engineer and the client to maintain the confidentiality of the information contained in the engineer’s report. In contrast, in the present case, there is nothing to indicate under the facts that an agreement exists between any of the parties to maintain the confidentiality of all or part of any reports prepared by the engineer.

Also in Case No. 89-7, there was the possibility of a dangerous condition developing at some point in the future, while in the present case, loss of life had already occurred. Importantly however, this circumstance needs to be contrasted with the circumstances in Case No. 89-7, where the client had essentially admitted serious code violations, while, in the present case, the possibility of a defect is merely a matter of speculation and surmise.

It is on this last point that the Board believes this case must hinge. Looking at the facts and circumstances in their totality, the Board is convinced that Sam acted reasonably under the circumstances by properly balancing the obligation of the engineer to be faithful to the client and not to disclose what might be considered by the client to be confidential information concerning the business affairs of a client without that client’s consent, and the obligation of the engineer to hold paramount the public health and safety.

The Board says this because there is nothing under the facts to indicate anything more than Sam’s general surmise and speculation about the cause of the structural failure of the wall. Sam’s observation appears to be based upon a visual inspection without anything more. There is nothing noted in the facts to indicate that Sam had expertise in structural engineering. While it may be appropriate for Sam to note such information in his field notes, to place this information in a final report would not be responsible and could unnecessarily inflame the situation. However, under no circumstance would it be appropriate for Sam to alter his field notes.

Also, while it might be appropriate for Sam to verbally report this information to Sam’s client, and for the client to report this information to the public agency, it is clear that Sam was retained to perform a specific task for which he was presumably competent. Clearly the prime consultant, which has overall responsibility for the project, is in a far better position than Sam to understand the interrelationships between various elements of the projects, including the history of previous work performed on the bridge, prior consultants, contractors, etc., in order to make an informed evaluation.

Therefore, the Board concludes that Sam did the appropriate thing in coming forward to his client with the information and also by documenting the information for possible future reference as appropriate. Under the circumstances it would have been improper for Sam to include reference to the information in his final report, particularly since it would have been based upon mere speculation and not careful testing or evaluation by a competent individual or firm. At the same time, the Board is of the opinion that Sam has an obligation to follow through to see that correct follow-up action is taken by the public agency. Only if the public agency does not take corrective action should Sam consider alternatives. Finally, for Sam to have reported this information to a public authority under the circumstances as outlined in the facts, before determining whether corrective action is taken, would have been an overreaction and could easily have risked jeopardizing the professional reputations of his client and the public agency.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was ethical for Sam to retain the information in his engineering notes but not include it in the final written report, as requested, and not report this information to any other public agency or authority as long as corrective action is taken by the public agency within a relatively short period of time.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

James G. Fuller, P.E.; William E. Norris, P.E.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Richard Simberg, P.E.; Jimmy H. Smith, P.E., Ph.D.; C. Allen Wortley, P.E.;Donald L. Hiatte, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

I voted not ethical, and I suspect many others will vote the same.

There was no mention in the scenario of “It was ethical … as long as corrective action is taken by the public agency within a relatively short period of time.”

Without that comment at the end, It sounded like Sam omitted a severe safety issue and never followed up.

To me, this is no different than when a medical doctor is faced with evidence of child abuse and is REQUIRED by law to report it, even if the parents of the child do not want exposure. An engineer’s primary duty is to society, not to the pocketbook of a client. It is only because of waffling by persons like those on this alleged ‘ethics’ board that there is any alleged ‘conflict’.

I am shocked that the Board said “ethical” in this case. It’s similar to the police discovering evidence of a crime in plain sight while legally searching for something else – do they ignore the law-breaking? Does Sam ignore the potential safety implications of what he discovered in carrying out his contracted scope of work? I say he should have provided written information about the potential safety issue to the proper authorities.

I agree with the first two commentators, It was unethical. The engineer’s first responsibility is to the health and welfare of the public; not the governing authority.

Umm… did the reviewers miss the point that the wall had already failed and a death had occurred? It should be intuitively obvious to the most casual observer that there was a structural problem. I recount the Columbia Disaster. The wizards at NASA were incapable of discerning that a five pound object traveling at 1200 mph (approx) could inflict damage on a brittle material (the Shuttle heat shield). NASA used YOUR logic, i.e. we could not prove that damage had occurred…Yet, even my non-tech flight students would be able to conclude that the noted object would have four times the force of the standard test chicken launched at 300 mph. Just because calculations were not done or tests run, it does not mean that an engineer is not required to draw reasonable inferences.

Glad this was not a question on an ethics course – I certainly would have missed it. It does not appear to me that the engineers in both cases went far enough to protect the public. Basing a decision on a prior case that was flawed resulted in a flawed decision in both cases.

I believe it was his responsibility to note the apparent deficiency in the report with appropriate caveats that it was based on a cursory observation and not his area of expertise. This would ensure that the concern was not lost. I would not have reported it to a public agency but no possible way it would not be in my report. One of the rare times I strongly disagree with the review board.

For me the critical fact was that the public agency responsible for the bridge is aware of the condition observed. So how does including the observation in the report further ensuring the responsible parties are aware of the condition, it has already been established the responsible parties are aware of the observation.

However, I also don’t see how noting the structural observation would be a problem. The analysis focused on Sam’s potential speculation as to what the observed condition meant regarding safety instead of just reporting what was observed. Correct, Sam shouldn’t speculate on engineering conclusions outside his area of expertise. But noting a condition (there was discoloration on the bolts, a bolt was not present in the 3rd hole) isn’t an engineering conclusion (the bolt corrosion makes the bridge unsafe or the missing bolt is non-compliant with safety standards), its a statement of fact. So Sam should stick to the facts observed and not make conclusions outside of his area of practice.

Sam is free to follow up with the responsible agency about the potential relevant structural observation without violating an ethical obligations to his employer if they believe there is a risk to the public.

As a trained design professional, our first duty is the safety of the public. In the refetenced case things are more complicated because of a sale. In this case it is very straightforward: note the apparent deficiency and state another engineer with the requisite skills must investigate. People lose trust in us and we abrogate our moral responsibility if we don’t do our duty without excuses. Not ethical!

The fact that Sam was a subconsultant to a professional engineering firm is key. Sam reported the matter to a party having engineering expertise (and ethical obligations of their own) as well as a direct relationship with the public agency. Once Sam brought the matter to the attention of his (expert) client, it was reasonable for him to consider the matter closed. So I agree with the Board’s conclusion, but strongly disagree with the Board’s statement that Sam had an obligation to follow through to see that the public entity took corrective action. Sam cannot be a solo self-appointed policeman of a public entity. That’s absurd.

Is it just me, or was this situation poorly written when it came to the critical timeline of events? Sam inspected presumably prior to the crash, but it sounds like he looked at his notes after the crash. Only after the crash did he realize the significance of his notes on the barrier and told people. If he had realized the barrier was a much bigger issue and said nothing to anyone prior to the crash, I’m sure the board would have had a completely different decision. I agree with others that if you saw something bad enough that you noted it, even if it was outside your scope, maybe you should have said something or brought it to someone’s attention that knows a little more about the expertise in question. I think if Sam was truly ignorant to what structural ramifications would result from the damage he observed, the board’s decision was probably right, but this seems to be a far stretch.

Interesting, I agree with Ben. I concluded that the crash happened BEFORE Sam looked at the bridge. Yet, I remember one time at Sikorsky aircraft, I was doing a preflight on the UH-60 for a test. I noted that a cable was disconnected. The flight was grounded. The cable connected to a pitch control surface on the back of the helo. The cable was re-connected and the flight flown. I reported the incident to my supervisor. BUT NO ONE looked at the bigger picture. A scant 2 months later, the same thing happened and the aircraft and three crewmen were lost. After a 2 year investigation and much engineering modification, the control surface was re programmed such that a LACK OF SIGNAL resulted in the control surface going to the neutral position. By the way, I dodged a bullet. I was supposed to be on the ill fated fligjht, but I was on Military Reserve Duty and a friend of mine took the bullet for me.

Scottish juries can reach three verdicts, guilty, not proven, not guilty. Not proven seems like a better conclusion for this scenario. Ethical (not guilty) seems like a stretch. Not ethical (guilty) seems to fit the facts as presented much better than ethical. It would be nice to see a follow up from NSPE on this. Did they say Ethical becasue there was not a Not Proven available?