This is the November 2023 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the November 2023 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on November 28.

Your opinion has been registered for the November 2023 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on November 28.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Mitch agrees to provide consulting services to RMF, Inc., in connection with the development of a new product for manufacture. He develops a preliminary report, which is approved, then develops the design for the product. Mitch and RMF, Inc., do not negotiate any terms in their agreement relating to the actual ownership of the design of the product. Neither takes any steps to seek patent protection. When the design reaches the production stage, RMF, Inc., terminates the services of Mitch in accordance with their agreement.

Thereafter, Mitch agrees to provide consulting services to SYS, Inc., a competitor of RMF, Inc. As a part of those services, he divulges specific information unique to the product designed for RMF, Inc.

What Do You Think? Was it ethical for Mitch to divulge specific information to SYS, Inc., unique to the product designed earlier by him for RMF, Inc.?

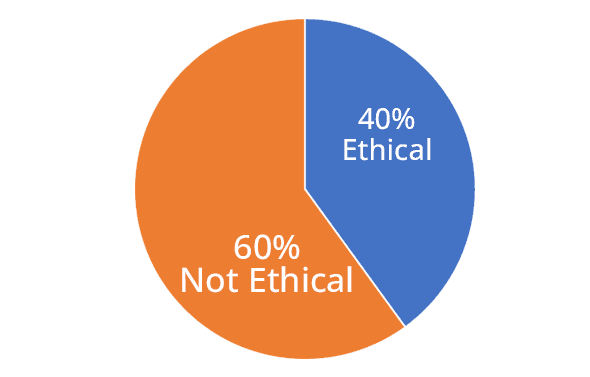

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

II.1.c

Engineers shall not reveal facts, data, or information without the prior consent of the client or employer except as authorized or required by law or this Code.III.4

Engineers shall not disclose, without consent, confidential information concerning the business affairs or technical processes of any present or former client or employer, or public body on which they serve.III.9.c

Engineers, before undertaking work for others in connection with which the engineer may make improvements, plans, designs, inventions, or other records that may justify copyrights or patents, should enter into a positive agreement regarding ownership.

Discussion

As with many provisions of the NSPE Code of Ethics, Code II.1.c. appears to be stated in a clear and concise way. It recognizes that the engineer has the obligation to refrain from revealing factual information obtained in a professional capacity without the permission of the client or employer except under certain specific circumstances. However, that is subject to a degree of interpretation.

From its earliest days, the Board has had to grapple with the meaning of the language contained in Code II.1.c. The Board faced Case 61-8 quite similarly to the instant one. That case involved an engineer who was employed by the ABC Company and assigned by his supervisor to develop processing equipment for the manufacture of certain chemical products. In his previous employment with the XYZ Company, the engineer had participated in the development of similar equipment. The technical information concerning the equipment had not been published in the technical press, or otherwise released. By virtue of his previous involvement in its development, the engineer was familiar with the equipment and the principles of its design. His supervisors in the ABC Company suggested that that knowledge of the particular equipment would be useful in developing similar equipment for their use and expected him to make it available to them.

In its decision on Case 61-8, the Board noted that most employers of engineers accept the obligation of permitting their engineers to decide for themselves what information they can carry and use from job to job, recognizing the ethical duty of the engineer not to disclose confidential information of a former employer. The Board concluded that inasmuch as the equipment developed for the XYZ Company had not been made known to the public or the industry, it was in the nature of a “trade secret” and the engineer who participated in its development may not ethically use or impart that particular knowledge to another employer without the consent of his former employer. He may, though, ethically apply general knowledge and general engineering principles gained in his former employment to solving the problems of ABC Company.

Although Case 61-8 is quite similar, it relates to the ethical obligation of employees, while the present case involves the ethical obligation of a consultant. However, that narrow issue is easily dispensed because all Code references pertaining to the ethical obligation of the engineer to maintain confidentiality refer to both the employer and the client. (See Code II.1.c. and Code III.4) This would clearly suggest that the drafters of the Code intended that the obligation to maintain confidentiality applies to the employed engineer as well as the consulting engineer. It is the Board’s view that consistent with Case 61-8, it would be unethical for Mitch to divulge specific information to SYS, Inc., unique to the product designed earlier by him for RMF, Inc.

It should be pointed out that if the information divulged is generally available within the industry then his conduct might be considered proper.

We note that since the rendering of Case 61-8, the NSPE Code of Ethics has been substantially modified. Of particular mention, in the context of this case, we refer to Code III.9.c., which admonishes engineers to take affirmative steps with employers or clients regarding ownership of patents or copyrights. In today’s highly mobile and competitive society, more and more employers are demanding, and employees are expecting, special terms of employment that will clearly spell out the duties and obligations of both with respect to confidentiality and rights relating to intellectual property. That approach is a positive one and will take some of the mystery out of these matters. Presumably, the ethical question raised in this case could have been more easily interpreted had Mitch and RMF, Inc., formally agreed to ownership of the design of the product.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was unethical for Mitch to divulge specific information to SYS, Inc., unique to the product designed earlier by him for RMF, Inc.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

Eugene N. Bechamps, P.E.; Robert J. Haefeli, P.E.; Ernest C. James, P.E.; Robert W. Jarvis, P.E.; J. Kent Roberts, P.E.; Everett S. Thompson, P.E.; Herbert G. Koogle, P.E.-L.S., chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

You have obviously not worked in Aerospace. An engineer is paid until they are not. Ergo, lacking contracts to the contrary, Mitch should be allowed to carry his knowledge and trade secrets with him – his brain is the storage place of the knowledge. Note that this case is why Polaroid split its camera products into three divisions – mechanical, chemical, and optical. Until one gets to the VP level, everyone is kept in one section only.

The fact that the original company did not make any attempt to specify the ownership of the design, nor has any plans to patent it means that the design is free to copy. The second company could purchase a product and reverse engineer it very easily and that is substantially no different than what Engineer Mitch did. If he was asked by the second company to design a similar product, and he believed that his first design was the best answer, it would be unethical for him to do a different design for the second client.

This scenario is poorly contrived as an instructional with too little detail to actually present a dilemma. The facts presented don’t comport with the conclusion that Mitch violated the code unless it is assumed he delivered something to SYS other than the design for the product he had previously developed. Quite the contrary.

1. Mitch and RMF, Inc., did “ not negotiate any terms in their agreement relating to the actual ownership of the design of the product.” Mitch was not required to do so by the code at III.9.c as it merely suggests but does not require such agreement, “Engineers, before undertaking work for others in connection with which the engineer may make improvements, plans, designs, inventions, or other records that may justify copyrights or patents, – should – enter into a positive agreement regarding ownership.” The use of “should” is not binding, and while the code and the review board certainly emphasize a best practice for self-protection of the engineer, a decision to not enter into a binding agreement is not an ethical or code violation.

2. The scenario states Mitch developed “the design for the product.” Absent a binding agreement otherwise, Mitch owns the design not RMF. The law granted Mitch a copyright for the work product that documents the design at the instant it was ‘fixed in any tangible medium of expression” – even if he does not take action to record such copyright. Therefore, as the owner of the product he cannot possibly violate the requirements of the code at II.1.c as long he only delivers the design for product which he owns by right. The code specifically protects him in this regard ”Engineers shall not reveal facts, data, or information without the prior consent of the client or employer – except as authorized or required by law – or this Code.” The law, 17 U.S.C. § 106, specifically authorizes Mitch to provide the entire product design and information about the design to SYS. PE Impact has already stipulated to these facts elsewhere on their site:

“In legal cases, the courts have held the default rule that the author retains the copyright if there is not a written agreement to the contrary. If a contract is created between two parties and there is not discussion about copyright ownership, the engineering firm (the author) will retain the copyright.

The owner of a copyright in engineering plans has three rights: the right to reproduce the plans, the right to prepare byproduct works based on the plans and the right to build the structure in the plans. And, the copyright owner also possesses the right to prevent others from exercising these rights.” (See https://peimpact.com/can-plans-and-drawings-be-copyrighted/ )

The 6th Circuit Court of appeals has recently affirmed in a similar case “The copyright protection extends to the drawing itself, affording Plaintiffs the exclusive right to prepare derivative works, distribute copies, and display the copyright”

3. Contrary to the assertion of the review board, the code at III.4 does not apply to the facts presented in this scenario. There is no assertion in the scenario that Mitch disclosed “confidential information concerning the business affairs or technical processes” of RMF. The scenario is limited to Mitch divulging “specific information unique to the product designed for RMF.” There is no mention of any transfer of information other than that related to the design itself, which is the product that Mitch owns and he sold to RMF. Therefore information specific to the – product – is not RMF’s confidential information. Notably Mitch may have accessed all manner of RMF’s confidential and propriety information in performing the analysis necessary to determine his product, the proposed design, was adequate and safe for the intended use. However, nothing in the stated scenario indicates such information was disclosed and certainly nothing in scenario indicates it was incorporated into the design documents delivered to SYS.

4. BER Case 61-8 cited by the board does not apply to the Mitch scenario. Mitch is not an employee of another company that ostensibly owned the intellectual property in question for that case. Contrary to board’s position that there is ambiguity in the ownership of the design, Mitch unequivocally the owns the IP in question. The copyright of the drafter attaches instantly to work upon it being recorded and remains with drafter until legally transferred, no legal ambiguity. In this case the IP is the documented design for a physical system. Mitch alone holds unlimited rights to that documented design. He has the right to sell that product, to anyone he chooses. He is just another engineer servicing the market of those that seek to “build to print.” The governing principles at play here are effectively the same as this scenario: RMF retained Mitch to design a product to hold open a particular door. Mitch analyzed the requirement and delivered drawings a for a wedge that RMF later built. SYS subsequently retained Mirch to design a product to hold open a similar door and Mitch delivered the same wedge drawings that he provided to RMF. Did Mitch commit an ethical violation ? Obviously not. He found two customers for his product, the plans for a build-to-print door wedge.

The conclusion that Mitch’s actions are unethical and a code violation is flawed, unless the board assumed facts not in evidence. Mitch does not act unethically when he delivers a design he previously produced and currently owns as the solution for a requirement presented to him by SYS. Such actions are in fact protected under the law by right and cannot be abridged by the code. However, Mitch does act foolishly from a business perspective. The board’s recommendation, that simply reiterated the suggestion of the code at III.9.c, is certainly correct.