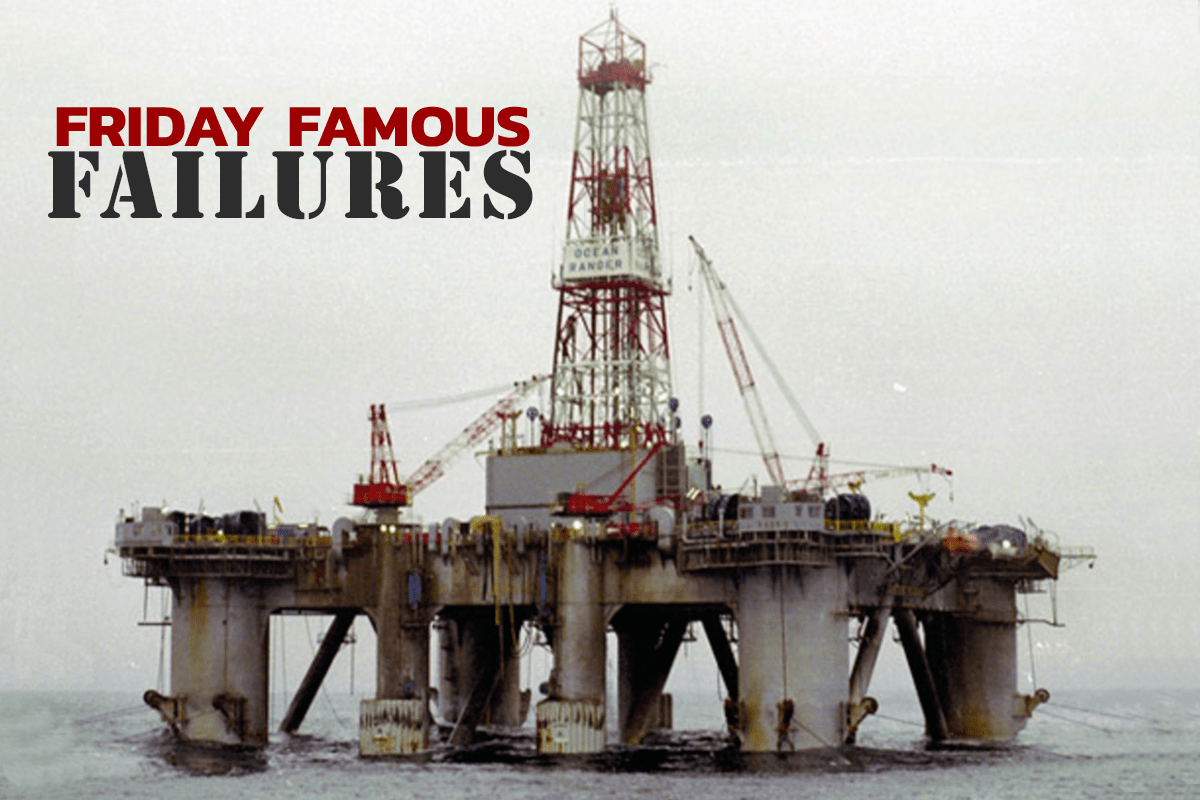

In February 1982, the Ocean Ranger was conducting drilling operations for ODECO off Newfoundland. The Ocean Ranger was a self-propelled oil-drilling platform that was capable of operating in 1,500 feet of ocean water and drilling to a depth of 25,000 feet. Built by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Japan, the Ocean Ranger was approved for “unrestricted ocean operations” and designed to withstand up to 100-knot winds and 110-foot waves at sea.

Yet in the early hours of 15 February 1982, during a violent Atlantic storm, the Ocean Ranger capsized and sank. The disaster resulted in the death of all 84 crew members. What had gone wrong with this immensely capable ocean vessel?

Timeline of the disaster

14 February 1982:

- 7:15 PM (approximately): A nearby oil drilling platform, the Sedco 706, overhears internal radio transmissions from the Ocean Ranger about a broken porthole and water in the ballast control room, including some discussion on how to repair the damage. The Ocean Ranger broadcasts a report of seas at 55 feet with occasional waves as high as 65 feet.

- 9:00 PM: The Sedco and another nearby oil platform overhear radio transmissions from Ocean Ranger, noting that the ballast control valves seemed to be “opening and closing of their own accord.”

15 February 1982:

- 12:52 AM: Ocean Ranger broadcasts a mayday call (notification of an emergency), reporting a serious list to port and requesting immediate assistance. The standby vessel MV Seaforth Highlander moves in to provide assistance.

- 1:00 AM: Military and company-owned helicopters take off to provide assistance.

- 1:30 AM: Ocean Ranger broadcasts “There will be no further radio communications from Ocean Ranger. We are going to lifeboat stations.” The crew attempts to evacuate.

- 3:10 AM: Ocean Ranger sinks.

What caused this disaster?

Equipment malfunction. The porthole broken by the large waves allowed seawater to ingress into the ballast control room, which may have caused the ballast control system to short out and malfunction, ultimately causing or increasing the list of the Ocean Ranger.

Flooding internal to the oil platform. As a result of the broken porthole and the forward list, the forward chain lockers located in the forward corner support columns began to flood. The flooding progressed and eventually reached the upper deck as the vessel tilted further and further, causing the vessel to capsize.

Design flaws in the ballast control system. The high degree of the forward list created so much vertical separation between the forward tanks and the ballast pumps astern that the ballast pumps were not able to achieve suction and thus were incapable of moving or discharging the accumulated water in the forward ballast tanks.

Lack of crew training. The crew lacked detailed instructions and training on the Ocean Ranger’s ballast control system. The crew at one point blindly attempted to operate the ballast control panel manually. Investigators speculated that the crew might have inadvertently increased the forward list of the vessel in their attempt to operate the system.

Lack of safety procedures and training. The crew was not trained in safety procedures (including evacuation), and in any case, the safety features of the Ocean Ranger were inadequate. Furthermore, there were no safety protocols for the standby vessels, which during the event, were unable to rescue any crew members that successfully evacuated.

Effects of the disaster

Investigators found that at least one lifeboat was launched from the Ocean Ranger with up to 36 crew inside, and witnesses on the standby vessel reported seeing at least 20 crew members in the water, which suggests that at least 56 crew made it into the water. The United States Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation report noted that “these men either chose to enter the water directly or were thrown into the water as a result of unsuccessful lifesaving [sic] equipment launching.”

The ongoing storm hindered any rescue attempts by the standby vessels. Investigators determined, however, that these standby vessels were neither equipped nor configured to rescue crew members from the frigid sea. The helicopters did not arrive on station until 2:30 AM due to the bad weather, at which point the Ocean Ranger’s crew had likely succumbed to hypothermia and drowned. After the disaster, only 22 bodies were recovered from the North Atlantic. Medical examinations proved that those men had died due to drowning while in a hypothermic state.

The United States Coast Guard and Canadian military forces searched for the Ocean Ranger for several weeks following the sinking. The wreckage was eventually found resting almost 500 feet south-east of the wellhead it had been operating before the storm. The main structure was surrounded on the ocean floor by the debris of major components that broke off during the sinking, including the derrick and the cranes.

The USCG’s Marine Board of Investigation into the sinking postulated the following sequence of events which caused the sinking:

- A large wave from the storm system broke a porthole in the ballast control room, which began flooding;

- Due to equipment malfunction or mistakes by operators, excess seawater from the flooding could not be evacuated from the forward ballast tanks, causing the Ocean Ranger to begin listing forward;

- At some point the forward list overcame the ballast control system’s ability to pump water from the forward ballast tanks;

- Sufficient forward list developed to flood the upper deck and cause the platform to capsize.

In addition to the USCG’s investigation, a Canadian joint Federal-Provincial Royal Commission also investigated the Ocean Ranger disaster for the next two years. The Commission’s findings were widespread and technical, and condemned in detail the lack of operator and safety training for the crew, the design flaws of the vessel (including the ballast control system), the lack of survival suits and other lifesaving equipment for all the crew members, and the ineffective inspection and regulation by the United States and Canadian government agencies.

The Commission concluded its report by offering recommendations to rectify the design flaws and improve lifesaving equipment on Canadian vessels and platforms engaged in offshore operations. The Commission further recommended that the Canadian federal government invest annually in research and development for search and rescue technologies, including improvements to lifesaving equipment. The Canadian government accepted this recommendation and has met its commitment to provide research funds for these activities in every fiscal year since 1982, the year of the disaster.

In August 1983, the wreckage of the Ocean Ranger was floated, towed to deeper waters, and sunk. There were several lawsuits filed against ODECO, the operator of the Ocean Ranger, and various government agencies; these were settled out of court in a package valued at $20 million.

A permanent monument to those who died in the sinking was established at the Confederation Building, the seat of the government of Newfoundland.

The ocean environment is not dangerous, but it is ruthless and unforgiving of human errot

They put a porthole in a compartment with equipment essential to the survival of the platform?