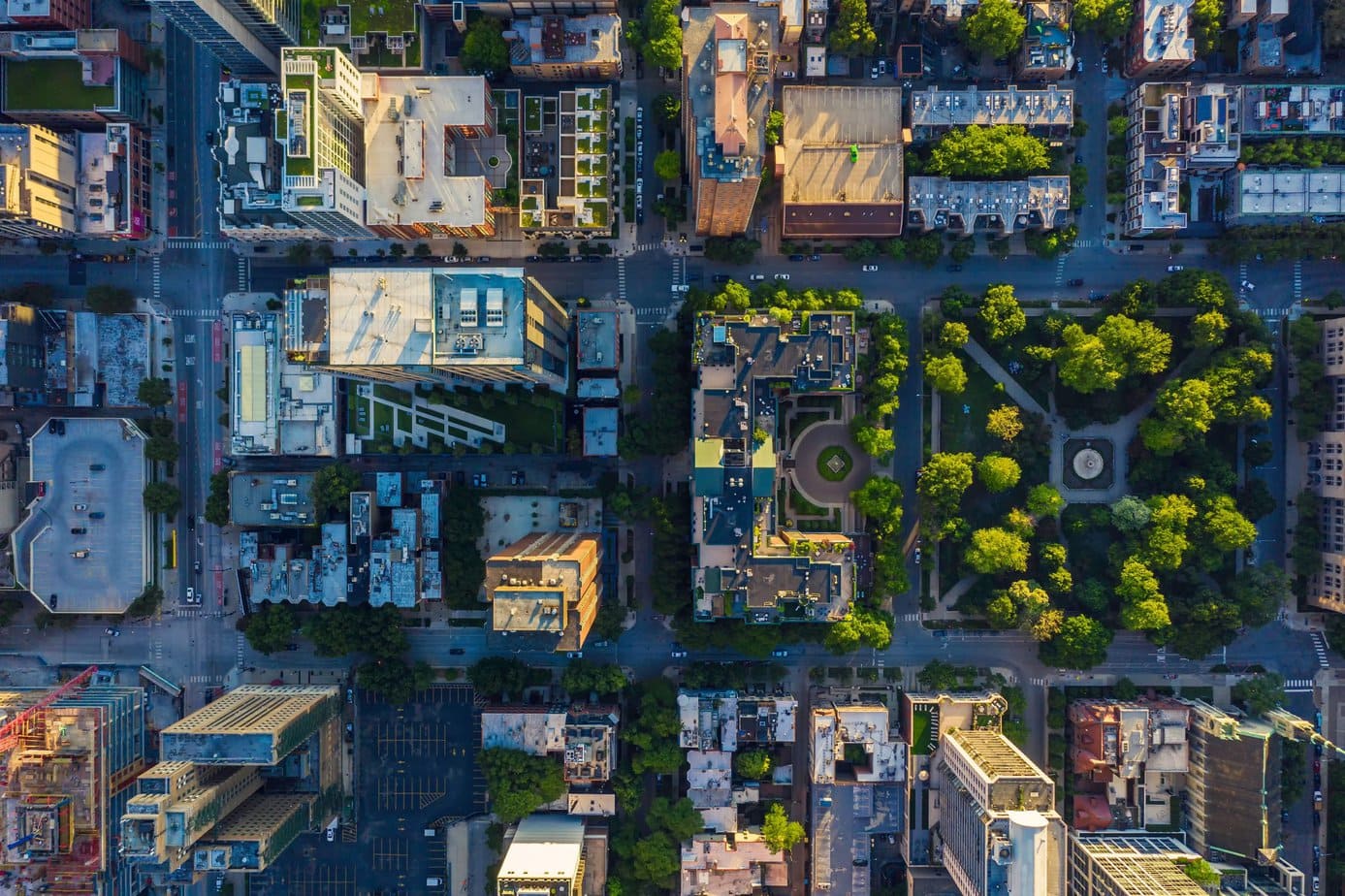

In urban planning, the grid plan, also known as the grid street plan or gridiron plan, is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a walkable grid. Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan—frequent intersections and orthogonal geometry—are designed to facilitate pedestrian movement. The geometry helps with orientation and wayfinding, and frequent intersections facilitate the choice and directness of routes to desired destinations.

The grid plan dates from antiquity and originated in multiple cultures. Some of the earliest planned cities were built using grid plans in the Indian subcontinent. So, why aren’t modern suburbs built on a walkable grid? To begin answering that question, we must first examine the concepts of walkability and Complete Neighborhood.

Walkability

Walkability refers to the ability to safely walk to amenities within a reasonable distance, usually defined as a walk of 30 minutes or less. According to the Walkable and Livable Communities Institute, a walkable community takes into consideration persons, not automobiles, at the center of the design scale.

For a place to call itself “walkable,” there needs to be enough within an individual’s walkshed that most trips (other than commuting) can be accomplished on foot. A walkshed is the area around a station—or any central destination—that the average person can reach on foot.

This is what the website Walk Score attempts to measure and ties back to the concept of Complete Neighborhoods—neighborhoods with safe and convenient access to the goods and services needed for daily living. This includes a variety of housing options, grocery stores and other commercial services, quality public schools, public open spaces and recreational facilities, affordable active transportation options, and civic amenities.

The Complete Neighborhood

An important element of a Complete Neighborhood is that it is built at a walkable and bikeable human scale and meets the needs of people of all ages and abilities. It has everything one would need—all within walking distance from home. For those who are fortunate enough to work from or close to home, it’s the sort of neighborhood one could go months without leaving. You’re not bound by a car, bicycle, or mass transit on a regular basis. Suburbs weren’t and still aren’t built for that.

Cities, with little exception to the rule, are Complete Neighborhoods that are street- and grid-based. They’re built for walkability. In fact, the concept of a walkable grid is a fundamental part of any urban transit-based system.

In order to measure walkability, the first question that must be answered is, “Where do you want to get to on foot?” If the answer is, “To my neighbor’s house who lives next door,” then every suburb could conceivably call itself “walkable.” But what about walking to work? Or to your favorite place to eat? By and large, you can’t do that in a suburb. Calling a place “walkable” is mostly a matter of saying you can access everything on foot. You can live, work, shop, go “out on the town,” and dine at your choice of restaurants. City/urban neighborhoods include all of that. And city living space comes in the form of apartment buildings, high-rise condominiums, and co-ops surrounded by shops, restaurants, entertainment, schools, recreation, and other amenities that are highly walkable.

The vast majority of suburban neighborhoods don’t offer that walkability. And, by virtue of their design and purpose, they simply can’t—yet.

Do you have any experience working with walkable grids or urban planning? Feel free to share your thoughts below.

The only way to create a walkable neighborhood is to have housing density sufficient to sustain local businesses such as groceries, hardware, etc.

Walkable neighborhoods with commercial cores and single-family homes were tried all over the country in the 1960s and 70s. Commercial course were not sustainable: commercial centers and office buildings have been demolished and housing built in their place.

When those same offices and commercial Sarah was built on the program of that neighborhood but available to other neighborhoods they were than sustainable but they still required automobile access from a single-family radius of 1 to 2 miles.

Living in a neighborhood that was signed on a grid, iot’d very walkable. The only challenge is my back which isn’t very walkable, var the planners haven’t figured out a way to solve that problem with neighborhood [planning.

My wife and I have four large dogs and for this reason we live in a suburb area where the homes have over an acre each. To walk around our neighborhood, you would go about 2 miles to cover the 40 some homes that are in our plate. This gives us room for the dogs and though we do drive to stores and other things, we like the space. City living would not work for us and the dogs, as they would not have room to run. So, to me it is a choice between how you wish to live, the space you wish to have and the convenance you would like.

Walkability of senior housing communities should be a no-brainer–in most single-family type senior communities I have been nearly everyone has a car and has to drive miles for groceries, services, and so forth. It would seem they could be designed adjacent to various commercial businesses that could cater to the general public on one side and connected to walking paths on the senior housing side so that the residents could access the stores by walking and biking safely. (And yes, there would be a road connection as well for those who would need to drive or plan buying more goods than they can carry.)

“city living space comes in the form of apartment buildings, high-rise condominiums, and co-ops surrounded by shops, restaurants, entertainment, schools, recreation, and other amenities”

It sounds like population density is the dominant factor – there needs to be enough population within the walkshed of the shops, restaurants, etc to support said shops, restaurants, etc. Suburban neighborhoods generally shun that density, so there generally isn’t the population within the walkshed to support those businesses without providing parking and driving access too (which then makes it less walkable, as well).

I love these types of conversations. As a engineer who designs these urban/suburban communities our hands are tied with regulations; zoning, design standards (lot width/depth, etc.), storm water infiltration requirements, road design standards, riparian buffers, environmental constraints and so on. All these regulations, although written with good intentions, spread our communities outward and hence not walk-able. Shame really.

In the US, suburban housing expansion began in the late 1800’s when electric utilities built streetcar lines beyond the developed urban cores, as a means to open up land for real estate development and consumption of electric power. By the 1920’s, the auto industry had grown car ownership to a point where better roads were needed. At the end of World War II, returning veterans could get VA loans to buy single family houses, which many preferred over apartments. The auto industry retooled from wartime production and marketed cars to everyone. Residential real estate development expanded beyond the core cities that required sidewalks and often, gridded street patterns. More rural areas outside the core city limits had less stringent requirements and often approved developments without sidewalks and curvilinear roads that did not follow gridded geometry. With larger residential lots and zoning that prevented mingling other land uses with residential development, dense grids were not necessary, especially since just about everyone had a car. Fewer intersections also allowed faster speeds for autos.

Planners now are aware that walkable streets and walkable destinations are beneficial in terms of active transportation (walking and cycling) and are trying to bring back walkable grids. Having to bus (or drive) all children to school is expensive and denies them the opportunity to get exercise by walking.

Today, however, more folks are taking advantage of micro-mobility devices such as scooters and E-bikes. These technolgies rely less on fossil fuels and may lead to more emphasis on more dense grids.

The City of Tucson, AZ was developed with major arterial streets with all commercial development on a one-mile square grid. Inside the grids were curvilinear streets with the schools and parks near the center of the squares. That seemed to work fairly well as long as everyone had their ticket to freedom (a car) to get to the commercial areas.

England decided that you either lived a dense city or on a large estate. Intermediate sized plots were banned so that individuals could not have their own 2-acre junk yard. That’s one of the reasons why our ancestors left England so that everyone had the freedom to spoil their little corner of the country as they saw fit.

We lived in a medium-sized town in Germany for 2 years, and it was very walkable. Weiden has a population of 42,000 today. It probably had close to that when we lived there 20 years ago.

We could walk from our house to a small grocery store, bakery, several restaurants, etc. in our neighborhood on the edge of town. It was very convenient, and the culture embraced walking for day-to-day needs.

The part I found most intriguing was the way they designed for pedestrians and cyclists. Our young sons could bicycle from our home on the outskirts of town right down to the city center, while only crossing one single small low traffic street. There was an “underpass” for pedestrians/cyclists that went under a major road, some paths along a river, and a couple of creative clover leaf type interchanges.

I have seen nothing like that in the USA, and I miss it. We could build this way if our zoning and construction standards valued this type of environment.