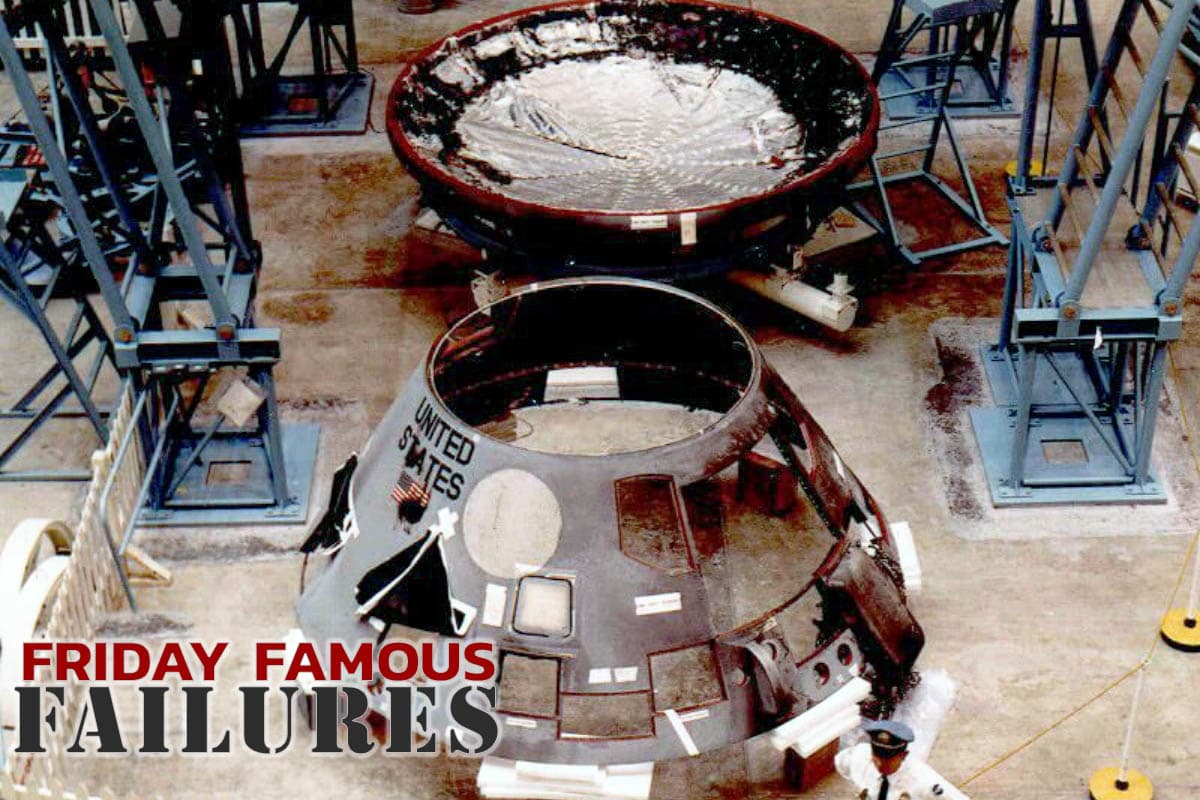

At the height of the space race in the 1960s, the United States pursued an accelerated program to put men on the moon before the Soviet Union. Apollo 1 was to be the first crewed mission of the United States Apollo program, the undertaking to land the first men on the moon. On February 21, 1967, Apollo 1’s three crew members, Command Pilot Virgil Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger B. Chaffe, were set to launch the first low Earth orbital test of the Apollo command and service model. But during a launch test rehearsal on January 27, a cabin fire broke out, and all three crew members perished inside. Immediately after the fire, NASA convened an Accident Review Board to determine the cause of the fire.

The command module was built by North American Aviation. Initially, NASA hoped to launch the Apollo Program mission alongside the final Gemini Program mission in November 1966. However, Apollo 1’s launch date was delayed to February 21, 1967, as its command and service module (CSM) was larger and more complex than previous spacecraft designs, and therefore took longer than expected to develop and build. In August of 1966, only months prior to the originally-targeted launch date, the Apollo 1 crew met with Spacecraft Program Office manager Joseph Shea to express concerns about the amount of flammable material in the cabin. In response, Shea directed his engineers to remove the flammable material.

A launch simulation was held on January 27, 1967, to test if the spacecraft could operate while detached from all cables. The test was considered non-hazardous because neither the launch vehicle nor the spacecraft carried fuel or cryogenics, and all explosive bolts were secured. Passing this test was crucial to making the February 21 launch date. The crew entered the command module in their pressure suits at 1:00 pm and were hooked up to the spacecraft’s oxygen and communication systems.

The simulation suffered several delays. First, the countdown was put on hold after Grissom reported a strange smell. A brief investigation found nothing amiss in the CSM. The eventual accident report found this smell unrelated to the fire. During hatch installation, communication troubles caused yet another delay. Nevertheless, by 6:20 pm, all countdown functions were completed, and at 6:30 pm, the count was at T minus 10 minutes.

After the simulation resumed, the CSM experienced a momentary increase in the AC Bus 2 voltage. Nine seconds later, one astronaut exclaimed that there was a fire. After some “scuffling” sounds, nearly seven seconds of silence followed. Then the ground controllers heard a garbled transmission about fighting a fire, and rescue efforts began. However, the intense fire, fed by the pure oxygen in the CSM atmosphere, ruptured the command module’s inner wall. Flames and gases rushed outside the CSM through access panels. Intense heat, smoke, and ineffective gas masks hampered the ground crew’s ability to rescue the men.

As pressure released because of the cabin rupture, the convective rush of air caused the flames to spread. It took five minutes for the workers to open all three hatch layers to try to rescue the men. By the time they were able to break through, the astronauts had perished. The primary cause of death for all three astronauts was cardiac arrest caused by high concentrations of carbon monoxide.

After the accident, NASA Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans established a Review Board that included astronauts and the director of the Langley Research Center, Floyd L. Thompson. Seamans also ordered all Apollo 1 hardware and software to be impounded. After investigating, the Board identified several factors that combined to cause the fire and the astronauts’ deaths.

Details Found From The Investigation

First, the fire itself was due to the combination of “vulnerable wiring carrying spacecraft power” and “vulnerable plumbing carrying a combustible and corrosive element.” The Board determined that the electrical power momentarily failed and found evidence of several electric arcs in the interior equipment. While they were unable to locate and identify the specific arc location that was the ignition source, they determined that the fire likely started near the floor in the lower-left section of the cabin. The Board also noted that silver-plated copper wire in the environmental control unit had become stripped of its Teflon insulation.

This weak point in the wiring ran near a junction in an ethylene glycol/water cooling line that had been prone to leaks. Four months after the accident, it was discovered that ethylene glycol solution combined with silver anode could initiate a violent exothermic reaction that would ignite the ethylene glycol mixture, particularly in the CSM’s pure oxygen environment. Later experiments confirmed this hazard existed for silver-plated wires, but not for copper or nickel-plated wires.

Second, the CSM was highly pressurized with pure oxygen. This was part of the plugs-out test to simulate the launch procedure. In this environment, materials not normally considered flammable become highly flammable and can burst into flames. This applied to 34 square feet of velcro carpeting recently installed in the CSM. While this material had been removed at the direction of Shea in response to the astronauts’ concerns from several months prior, it was reinstalled prior to the simulation.

Third, the high pressure in the CSM made it impossible to open the hatch and allow the astronauts to escape, as a high amount of force held it in place due to the pressure differential. To allow for emergency egress, NASA engineers had added a cabin vent valve that would depressurize the CSM and allow the hatch to open normally. However, the wall of flames resulting from the fire made the cabin vent valve impossible to reach, and the pressurized CSM essentially locked the astronauts in with the fire. Originally, North American Aviation designed the hatch to open via explosive bolts in an emergency (much like an ejection sequence in an airplane), but NASA was afraid the explosive bolts would accidentally jettison the hatch and opted for mechanical operation in emergencies permitted by the cabin vent valve.

Fourth, because the simulation was not considered a hazardous test, there were no fire, rescue, or medical teams in attendance, and the work area was not cleaned or organized. As a result, ground crews and emergency personnel experienced many delays in attempting a rescue, including physical obstacles, steps, and sharp turns in the test facility. Further, the Board found the firefighting capabilities to be inadequate to fight a fire made so much more intense by the pressurized pure-oxygen environment.

The fire in Apollo 1 exposed many engineering flaws in the spacecraft and resulted in widespread criticism of NASA and the space program. As a result, the command module was grounded and redesigned, which delayed the program for more than two years. There are a number of memorials that honor the crew of the failed mission, including landmarks, schools, and even a planetarium.

These three pioneers gave their life which resulted in better engineering and in more safety measures.

Sadly it often takes an accident to get the job done properly.

This analysis of the Apollo fire disaster is the phenomenal insight required when designing and implementing such critical equipment. You really should have two groups come up with different ideas and concerns, pros and cons, when completing any design with so many potential hazards. Everything, no matter how simple, must be considered.

PDHEngineer.com’s course #ET-1035 (Engineering Ethics: The Challenger Disaster and the Story of “The Five Lepers”) covers a similar NASA failure – the Challenger Disaster – which occurred in the earlier days of the space shuttle program. A similar outcome to the above mentioned Apollo 1 incident occurred when developing the next generation space vehicle (to the Apollo space vehicles), namely the space shuttle.

Although the PDHEngineer course ET-1035 is not free, there are supplemental documents available online on this topic. Chapter IX, “The Challenger Accident”, of the Government publication — NASA SP-4313: Power to Explore: A History of the Marshall Space Flight Center 1960-1990 provides good details leading up to and causing the Challenger Disaster.