This is the December 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the December 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on December 28.

Your opinion has been registered for the December 2021 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on December 28.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Adam is employed by SPQ Engineering, an engineering firm in private practice involved in the design of bridges and other structures. As part of its services, SPQ Engineering uses a CAD software design product under a licensing agreement with a vendor. Although under the terms of the licensing agreement, SPQ Engineering is not permitted to use the software at more than one workstation without paying a higher licensing fee, SPQ Engineering ignores this restriction and uses the software at a number of employee workstations. Adam becomes aware of this practice and calls a “hotline” publicized in a technical publication and reports his employer’s activities.

Was it ethical for Adam to report his employer’s apparent violation of the licensing agreement on the “hotline” without first discussing his concerns with his employer?

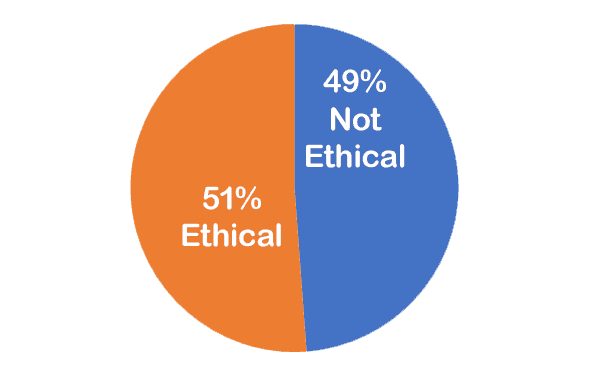

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code II.1.c:

Engineers shall not reveal facts, data, or information without the prior consent of the client or employer except as authorized or required by law or this Code.

Code II.1.f: Engineers having knowledge of any alleged violation of this Code shall report thereon to appropriate professional bodies and, when relevant, also to public authorities, and cooperate with the proper authorities in furnishing such information or assistance as may be required.

Code II.4: Engineers shall act for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.

Code III.9: Engineers shall give credit for engineering work to those to whom credit is due, and will recognize the proprietary interests of others.

Discussion

The facts and circumstances involved in this case are probably most analogous to earlier Board of Ethical Review cases dealing with the issue of whistleblowing.

Over the years, the Board has considered cases relating to the issue of whistleblowing. The first, BER Case No. 82-5, involved the issue of whether an engineer had an ethical obligation or an ethical right to continue his efforts to secure a change in the policy of his employer or to report his concerns to the proper authority. The case related to an engineer, employed by a large industrial employer, who, after observing that certain subcontractor plan submissions were inadequate, notified his employer of the problem. Following several notifications to the employer, which were ignored, the engineer became insistent regarding the problem, with the result that the employer placed a critical memo in the engineer’s file and ultimately placed the engineer on probation and at risk for possible termination.

After reviewing earlier BER cases and appropriate NSPE Code provisions, the Board noted that the facts before it did not relate to a danger to the public health and safety, but were premised upon a claim of unsatisfactory plans and the unjustified expenditure of public funds. The Board concluded that in the type of situation presented in Case No. 82-5, the ethical duty or right of the engineer becomes a matter of personal conscience. The Board was not willing to make a blanket statement that there is an ethical duty in these kinds of situations for the engineer to continue his campaign within the company and make the issue one for public discussion. Said the Board, “the NSPE Code only requires that the engineer withdraw from a project and report to proper authorities when the circumstances involve endangerment of the public, health, safety, and welfare.”

In Case No. 88-6, which involved a city engineer who learned of wastewater ponds overflowing into a river, the Board, in reviewing the reasoning in Case No. 82-5, concluded that the facts involved a danger “to the public health and safety—the contamination of a community water supply.” On that basis, the Board, tracing its rationale in Case No. 82-5, noted that where an engineer determines that a case may involve a danger to the public safety, the engineer has not merely an “ethical right” but has an “ethical obligation” to report the matter to the proper authorities and withdraw from further service on the project.

Importantly, the Board acknowledged that it is difficult to say exactly at what point the engineer should have reported her concerns to the appropriate authorities. However, it was suggested that such reporting could have occurred when the engineer was reasonably certain that no action would be taken concerning her recommendations and that, in her professional judgment, a probable danger to the public health and safety existed.

We believe these two cases are instructive and relevant to the matter presently before the Board, for at least two significant reasons. First, the two cases draw a clear distinction between those matters that involve possible apparent improprieties and those that involve a probable or imminent danger to the public health and safety. Although not stated directly in either earlier case, adding further support to this basic principle is the fact that the language in Code II.1.f. is within the Rule of Practice section specifically relating to the engineer’s paramount obligation to protect the public health and safety.

Second, the circumstances involved in both BER Case Nos. 82-5 and 88-6 appear to involve situations where the engineers have at least made an effort to exhaust all internal mechanisms before contemplating taking action by reporting the dangers to the proper authorities.

Under the facts in the present case, the Board concluded that the facts and circumstance are not of a character that involves any danger—direct or indirect—to the public health and safety. Instead, the facts and circumstances relate to matters of a legal nature and do not relate to engineering judgment or expertise.

Code II.4 places a basic obligation on engineers to be faithful agents and trustees in professional matters with their employers. It is the Board’s opinion that Adam’s actions in reporting his employer’s apparent violation were directly in conflict with the NSPE Code of Ethics. We are troubled that Adam did not consider other less adversarial and surreptitious alternatives. For example, Adam could have first discussed this matter with his employer, pointing out the possible damages that the violation posed to SPQ Engineering, and suggesting that SPQ Engineering confers with its legal counsel before continuing its current actions.

Instead, Adam took a course of action that could cause significant damage to SPQ Engineering and ultimately to Adam himself. One is inclined to wonder about the motivation for Adam’s actions without his first exploring other less adversarial and surreptitious alternatives, in view of the lack of any direct danger to the public health and safety. While, in the context of the facts of this case, we cannot conclude that this provision compels Adam to ignore an apparent violation of the law and the NSPE Code (See Code III.9), by the same token, Adam could have easily exercised far greater judgment and professional discretion before taking action.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was not ethical for Adam to report his employer’s apparent violation of the licensing agreement on the “hotline” without first discussing his concerns with his employer.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

James G. Fuller, P.E.; William E. Norris, P.E.; Paul E. Pritzker, P.E.; Richard Simberg, P.E.; Jimmy H. Smith, P.E., Ph.D.; C. Allen Wortley, P.E.; Donald L. Hiatte, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

EXCUSE ME!!! Theft of intellectual property is a CRIME. NOT reporting this theft is, in fact, being an accessory.

So the board condones piracy in this hypothetical case, Is not illegal activity unethecal in and of itself? Also shame onthe software company for not creating a better licensing key or software to prevent the use by more seats than what has been purchased / licensed.

Sure the employee should have brought this up to his employer – perhaps he did and they ignored it. Many of these “hypothetical” cases don’t provide all the facts for us to make a truly informed decision. I still think it was ethical of the employee to inform the software company.

Seems to me that the firm was stealing from the firm (software Co.) and making money using the software at numerous stations. I agree that Adam should have chosen a lesser approach.

Is there a difference from stealing from the software company versus a client?

From the software developer’s standpoint, this was ethical. They have a user licensing agreement that states you need multiple licenses if running on multiple computers. The user is responsible for knowing the terms of the agreement and should be held to it. That’s why they have the hotline to report this type of practice in the first place.

From the company’s standpoint, and the rest of us reading this scenario, Adam seems to have jumped the gun with no risk of danger or safety to the public. He did not do his due diligence to attempt to solve the problem at the lowest level, but instead took an immediate nuclear option that will likely result in large fees and possibly court costs. The person that signed the agreement may not have known the practice was going on, or employees not privy to the agreement were unknowingly violating the agreement. I would lean more toward smart vs dumb decision instead of ethical vs not ethical for this case.

Ethical or not; I question the ethic of the software developers who discontinue support of their products to clients on products that have been paid for and used as agreed to in the original purchase contract.

Without looking at the code before I answered, I considered that thought that Code II.4 had to govern here. Another point is that the issue is between the vendor and SPQ. Adam’s information may be true, but for starters: adherence to the licensing agreement is not contingent on information or lack thereof from anyone else.

Ethics ate ethics and not bounded by “legal “ vs “impending hazard “.

Your setup clearly indicates that SPQ is willfully avoiding the additional fee and in this day and age it is common for licensers to proactively push “whistle blower” provisions for just this case. If Adam was wrong and SPQ had been paying for the additional services no harm done; if not they deserve the consequences.

I find the board’s logic here ponderous. If your conclusion is to be upheld, no-one should ever be a whistle blower. I strongly disagree.

Michael P Anderson, PE.

I disagree with the Board’s finding in this case. Software licensing agreements such as the one described are common in the industry and the choice to use the software outside the bounds of the constitutes theft of services. As an industry based primarily on intellectual efforts we should be diligent about the protection of intellectual property rights. The case stated that they ignored the licensing restriction, not that they were unaware of their violation.

I must agree with some of the comments already left here. An initial internal approach with a softer dialogue would have been preferable, but the setup to your problem implied a willful transgression by the employer. Regardless, it’s hard to believe many professionals would not be aware of such a restriction on software in this day and age. To deem whistleblowing on a clear-cut case of IP theft is troubling, at best.

The employer Acted correctlny in firing. Specially, since he did not discussed it with the employer

I disagree with this decision for similar reasons to David West’s final statement.

The case states that the SPQ Engineering ignored the licensing agreement. To ignore something is an intentional act. The choice of phrasing in this hypothetical means that SPQ Engineering is aware of the licensing agreement and are intentionally disregarding it. This interpretation is reinforced given the nature of all CAD software packages that I’m currently aware of: license management is fairly advanced and would require some significant effort to circumvent.

Engineer Adam becomes aware of this practice and based on this hypothetical also has the knowledge that SPQ Engineering is ignoring the license and not just unaware of the terms. This implies there has already been some sort internal discussion.

Adam should talk with the employer’s admin/manager prior reveal this issue.

But the question is this:

What Adam should do when the firm manager refuses to deal with this subject as unethical behavior?

Bigger issue is the firm already applied their “greater judgment and professional discretion” and were willing to risk causing “significant damage to SPQ Engineering” when intentionally violating this user agreement. I hope Adam moved to a more ethical firm before blowing the whistle.

Like many of the other commenters here, I find the review panel’s conclusion troubling and wrong. The engineer has no duty to turn a blind eye to his employer violating a licensing agreement (and apparently also committing IP theft from the software company). While talking to his employer first may have been a courteous thing to do, the engineer opens himself to potential retaliation by his employer. The firm has demonstrated that it is willing to act unethically, so it would not be unreasonable for Adam to conclude that it may also bad mouth him to potential future employers if he tries talking to them first and gets ignored.

While I do believe that Adam had a responsibility to notify his employer first about the “theft”, the article makes it very clear that the Company already knew about this and “ignored” the issue. While it is not a matter of life safety at this point, it is a crime. I would think at the heart of ethics is personal conscience. Perhaps he should have reminded the Company first, but it seems contrary to me to say that it is unethical to report the Company.

I am surprised so many of the comments do not deal with the requirement that the individual advise his employer that they are violating a licensing agreement. They may not be aware of that circumstance. An individual officer may be doing this willfully outside of policy, or records may have been lost. The company has to be advised and allowed to demonstrate their intent, if they shrug their shoulders, say so what, and blow it off, that’s a different story. Absence of Malice is a legal standard Engineers need to get acquainted with.

Perhaps Adam could have left a polite anonymous letter to his employer to remind them of their apparent lapse, saying that the situation gives him an ethical dilemma, and that it not corrected (e.g. in a few week), the hotline will be called.

So next time you see a thief running down the street with your neighbors TV, do the ethical thing and invite him to sit down and have a discussion about what has led him to make a bad choice rather than call the cops. Methinnks the ethics board might have reached a different conclusion if it was their intellectual property being stolen,

Well decades ago, when my employer asked me to copy software on numerous computers I asked if it was OK if I stole from him. That fixed it. Sometimes employers need to be educated. Move on if that does not work.

While I did not see a clear violation of “ethics”, I do see a crime. If he had already brought this up to his employer and been told in essence, “Yeah, we know but we are ignoring it, it is time to immediately start looking for another job. The company has proven themselves to be dishonest. When looking, it would be a very good idea to ask your potential employer their practices in this area. Working for a dishonest company will eventually bite you, and possibly render you unemployable as an engineer if you end up, whether rightly or wrongly, wearing any of the dirt when the dishonest / illegal acts come to light.

I also disagree with the Board of Ethical Review. As stated in previous posts, this is theft of another firm’s intellectual property. Would the Board’s decision be different if instead of software theft, we were talking about the unauthorized use of another firm’s typical detail library? If an engineer takes intellectual property from his employer and uses it to personally profit or uses it with a subsequent employer that is considered unethical action by the employee. This decision is seeming to imply that in such a case that the employee’s action is unethical, but the employer’s action is not.

I fear the results of the survey mirror the current attitude of the nation. Half clearly agree a crime was reported; half seem okay with the crime not being reported.

Surely we can agree on right and wrong ; I hope for our future. I am very disappointed with the Board. Perhaps they need to more carefully review the set ups. This clearly indicated the company knew it was stealing.