This is the July 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials, and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the July 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on July 23.

Your opinion has been registered for the July 2024 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on July 23.

A Review of the Facts

The City of West Eastville requests proposals from various consulting engineers for a major job that it is planning. Engineer Alan, a principal in a large engineering firm in West Eastville, decides to have his firm submit a proposal. Alan asks an engineer on his staff, Engineer Brad, to develop the proposal for the firm. Brad develops a proposal which is ultimately submitted to the city.

Soon thereafter, the city learns that Brad is the engineer who actually developed the proposal for the firm. A city official approaches Brad and asks if he would agree to a contract as a consultant, independent of Alan’s firm. Brad discloses the facts to Alan, resigns from the firm, and negotiates and enters into a contract with the city.

What Do You Think?

Was it unethical for Brad to agree to a contract for consulting services independent of Alan’s firm?

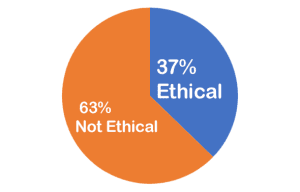

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

II.4

“Engineers shall act for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.”III.4.a

“Engineers shall not, without the consent of all interested parties, promote or arrange for new employment or practice in connection with a specific project for which the engineer has gained particular and specialized knowledge.”

Discussion

Over the years the Board has been faced with a number of cases with facts similar to those present in the instant case. In Case 77-11, the Board ruled that an engineer who left the employ of a firm and founded a new firm, contacting the clients of their former firm, did not violate the Code of Ethics.

However, we found that the engineer was in violation of the Code with regard to projects for which he had particular knowledge while in the employ of the firm. As we understood the facts then, the engineer did not undertake promotional efforts with the former clients of the firm while in the employ of the firm, nor did he engage in negotiations for work while in the employ of the firm. We assumed that the engineer possibly discussed with others the idea of soliciting work from former clients of the firm while still in its employ, but under a literal reading of that part of the Code, that degree of activity did not constitute a violation of the Code. However, we noted in Case 77-11 that such was not nearly so clear with regard to the latter portion of then-Code 7(a) (now Code III.4.a.) as related to practice in connection with a specific and specialized knowledge. We therefore found a violation of the Code provision.

Similarly, in Case 79-10 where an engineer employed by a firm that was winding down its operations sought to offer his services to complete projects under his own responsibility and risk without the concurrence of the principal of his employing firm, we ruled that such a course of action would not be unethical. We did not construe the broader aspect of then-Code 7(a) as barring Engineer A from taking the step he contemplated if the client should agree to it. We noted that the thrust of Code 7(a) was that an engineer would not initiate self-promotional efforts to take over projects in which he has been involved while in the employ of another. In Case 79-10, however, the engineer did not initiate the idea of taking over the work of the projects; the idea was set in motion by his employer’s proposed action. Accordingly, we found that the engineer would not be considered as attempting to compete unfairly under the principles embodied in the Code.

Reading both Case 77-11 and Case 79-10 suggests a need to balance (1) the interests of the firm and its interest in maintaining business goodwill with its clients, (2) the interests of the individually employed engineers, and most importantly (3) the interests of the client in retaining the firm of his choice. Obviously, the last interest is the most overriding interest of all. (See Code II.4) No one can deny that a client has a right to retain the engineering firm of his choice. What must be addressed, however, is a method of effectuating that right in a manner that is both fair and equitable to all of the concerned parties.

We are of the view that whereas here a client approaches an employed engineer who has been performing services for that client and initiates a request for services from the engineer independent of the firm, it would not be unethical for the engineers to agree to contract for professional services.

We reach that conclusion here for two basic reasons. First, there does not appear to be any indication under the facts that Brad had gained any “particular and specialized knowledge” which is required for a violation of Code III.4.a. We interpret the term “particular and specialized knowledge” narrowly in this context to mean unique and unusual information relating to certain specialized processes or trade secrets which are almost proprietary in nature. Were we to interpret “particular and specialized knowledge” to embrace, for example, any information relating to the work, we would be compelled to find the conduct of Brad to be unethical. However, we have chosen not to reach that finding inasmuch as most proposals are general in nature.

On our second point, this case, like many before, involves a variety of considerations that must be balanced. In this context, we note that the facts here presented involve a client who has made a determination that he would like to proceed in a professional relationship with an engineer of his choice. It cannot be disputed that the essential purpose of the Code of Ethics is to protect the interests of the public and in particular the interests of clients in their relations with members of the profession. When faced with a situation where the Code of Ethics can be interpreted to protect either the interest of an engineer or the interests of the public or the client, barring unforeseen circumstances, we are compelled to find in favor of the latter. For us to hold otherwise would be to obstruct the ability of an individual client to select those engineers of his choosing to perform professional services on his behalf.

Although not indicated by the facts, we can foresee a situation where a client would not want to continue a relationship with an engineering firm but would like to retain the services of individual members of the firm. As we have noted many times, the Code of Ethics applies to individual members of the engineering profession and not to others. While we view the city official’s actions with some reservation, where a client initiates contact with individual employees of a firm and seeks to retain their services, we do not think the Code of Ethics should be interpreted to deny the right of a client to undertake such action.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

A strict interpretation of the Code under the facts of this case leads us to conclude that it would not be unethical for Brad to agree to a contract for consulting services independent of Alan’s firm.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

F. Wendell Beard, P.E. Robert J. Haefeli, P.E. Ernest C. James, P.E. Robert W. Jarvis, P.E. James L. Polk, P.E. J. Kent Roberts, P.E. Alfred H. Samborn, P.E., chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

Brad was paid by his employer, and used his former employer’s resources to develop the proposal. You’re twisting yourself in knots to make this OK but it is not. As his former employer. The Board is out to lunch on this one. Brad needed to make his own proposal using his time and money on a different project.

I tend to agree with the concept that Engineer Alan’s firm paid for the proposal created by Engineer Brad (and employee), and therefore it is suspect that Engineer Brad solely reap the reward of a contract that Engineer Alan’s firm was attempting to acquire.

I agree with the earlier respondents that Brad was not fair to his employer who paid for his time to research the requirements for the new project and may have used resources that may not have been otherwise available to him had he not been employed by Alan’s firm. I believe it would have been more ethical had Brad first tried to negotiate a contract between Alan’s firm and the city.

Alan had full disclosure to both Brad and the city that he would be working for.

The part that I think Brads firm May want to check on is if anything from that written proposal Allen prepared before he left has been implemented in this project.

If Brad was employed by Alan under an “at will” arrangement, as in most jurisdictions, Brad is free to leave Alan’s employ at any time, as Alan is free to terminate Brad’s employment at any time. As such and considering that “non-compete” clauses are generally held invalid, Brad is free to pursue any and all work once not employed by Alan.

Alan to Brad – Good Riddance.

I see no way this could be decided without knowing if the proposal was accepted prior to Brad being approached in which case he would have to disclose to his employer and if he did not get permission his behavior would be unethical.

If the offer came after acceptance of the proposal by the City it would depend on Brad’s roles and responsibilities for seeing the agreed upon work to completion. If the consulting role would result in Brad being paid for these and his employer not being paid for these his behavior would be unethical without permission from his employer.

If the city is looking to pay the employer the full price proposed and Brad “extra” Brad’s authority and responsibility as a consultant would have to be acceptable to Brad, the city, and the employer.

in implementing .