Why It Happened in Wyoming

Who was the first person in the United States to receive an engineering license, and why did the very first licensure law happen where it did?

The short answer is Wyoming, 1907, and a man named Charles Bellamy. The longer answer is a story about water rights, unreliable technical documents, and a state engineer who believed the public deserved better safeguards when relying on engineering work.

The World Before “Professional Engineer”

Professional engineering licensure is a relatively modern concept. For most of the 1800s and into the early 20th century, the title “engineer” was not protected. That lack of regulation was manageable when engineering projects were small, localized, or informal. However, by the turn of the 20th century, the United States was rapidly expanding its infrastructure. Railroads, bridges, mines, municipal water systems, irrigation works, and early urban utilities were being designed and constructed at an unprecedented scale.

As engineering work became more complex and more consequential, a serious problem emerged. Individuals with little or no engineering training were producing technical documents and representing themselves as engineers to government agencies and the public. In Wyoming, State Engineer Clarence Johnston observed that lawyers, notaries, and other non-engineers were preparing and signing maps and plans submitted to the state, particularly documents related to water rights and water infrastructure.

This issue was especially critical in Wyoming. In an arid state, water was not merely a commodity; it was essential to economic development and survival. Errors in maps, surveys, or technical submittals could lead to misallocated water rights, legal disputes, failed infrastructure, or unsafe conditions. The consequences of poor engineering work were tangible and immediate.

1907: Wyoming Establishes a Standard`

In response to these concerns, Johnston and his colleagues advanced legislation during the 1907 session of the Wyoming Legislature. The resulting law required individuals representing themselves to the public as engineers or land surveyors to be registered with the state. It also established a state board to oversee qualifications and enforcement.

The principle behind the law was straightforward: if someone was going to offer engineering services to the public, that individual should meet a minimum standard of competence and accountability. This idea became the foundation of modern professional engineering licensure.

As with most regulatory reforms, resistance was swift. Standards are often inconvenient to those who benefit from the absence of oversight. Nevertheless, the law was passed, and its effects were quickly noticeable. Writing decades later, engineering historian Doug McGuirt noted that Johnston later remarked how the quality of maps and plans submitted for permits improved dramatically within months of the law’s implementation. When competence and accountability were required, technical submittals became more reliable almost immediately.

August 8, 1907: The First License Is Issued

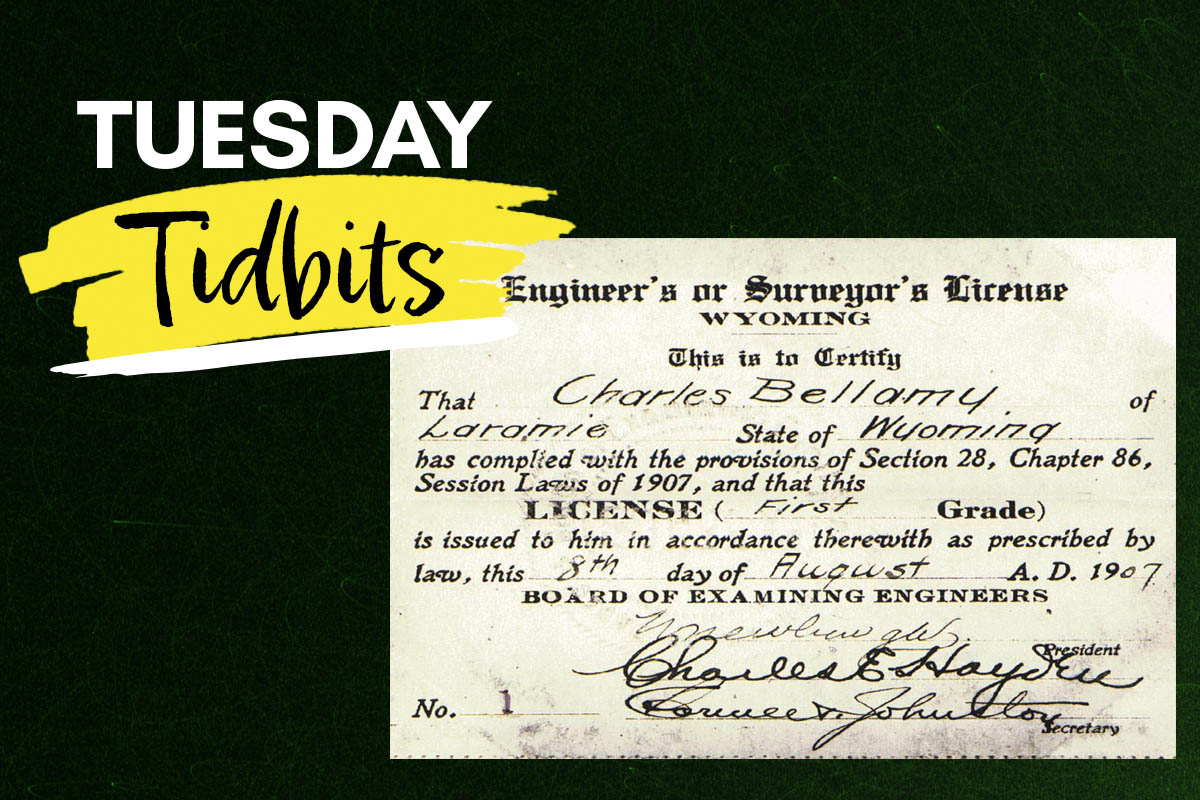

The milestone most often cited occurred on August 8, 1907, when Wyoming issued what is widely regarded as the first professional engineering license in the United States. The license was granted to Charles Bellamy.

According to historical records summarized by McGuirt in Professional Engineer magazine, Bellamy was a 52-year-old engineer and mineral surveyor at the time. Early licensure laws commonly grouped engineering and surveying together, reflecting the realities of professional practice in the early 1900s. Boundary determination, elevations, drainage, alignments, irrigation routes, mineral claims, and mapping were closely interconnected, particularly in developing western states.

Who Was Charles Bellamy?

While Bellamy is not a household name, available historical records provide insight into his professional role. Wyoming historical sources identify him as a civil engineer who also served as the first water commissioner under State Engineer Elwood Mead.

This combination of responsibilities, engineering, surveying, and water administration, was emblematic of professional practice in Wyoming at the time. As the state formalized its water rights system and developed irrigation and infrastructure projects, Bellamy’s work required technical judgment, practical experience, and a high degree of public trust. These are precisely the qualities professional licensure was intended to recognize and reinforce.

Bellamy’s family history adds a noteworthy footnote. His wife, Mary Godat Bellamy, later became known as Wyoming’s first woman legislator, underscoring the Bellamys’ place in the early civic and professional life of the state.

Why the First License Still Matters

Wyoming’s 1907 engineering licensure law was not about prestige or professional exclusivity. It was about protecting the public and improving the reliability of technical work used to make public decisions. Modern discussions of licensure history, including those published by ABET, emphasize that Johnston’s core concern was public trust; the public needed assurance that engineering work was being performed by qualified and ethically accountable professionals.

That same principle underlies professional engineering practice today. Concepts such as responsible charge, competency, ethical obligations, and the duty to protect public health, safety, and welfare all trace their roots to this early recognition that engineering decisions carry real consequences.

From State Regulation to a National Profession

The story of the first engineering license also illustrates how professional standards spread in the United States. Engineering licensure remains state-based, but over time, it has become a national expectation. While California enacted the first surveying licensure law in 1891, Wyoming’s 1907 engineering statute marked a turning point for the engineering profession.

As more states adopted licensure laws, the need for coordination and uniformity grew. This eventually led to the formation of a national organization, now known as the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying, in 1920. NCEES helped establish consistent examination standards, reciprocity principles, and professional mobility across state lines.

Conclusion

Should the public be expected to guess whether the person calling themselves an engineer is qualified?

Wyoming answered that question in 1907. By issuing its first engineering license to Charles Bellamy on August 8 of that year, the state set in motion a system of professional accountability that continues to define engineering practice today.

And when did Charles Bellamy take his first NCEES exam?

I find it interesting that this event was not due to an engineering failure that cost lives but started as a concern for ethics and public confidence. Well done!