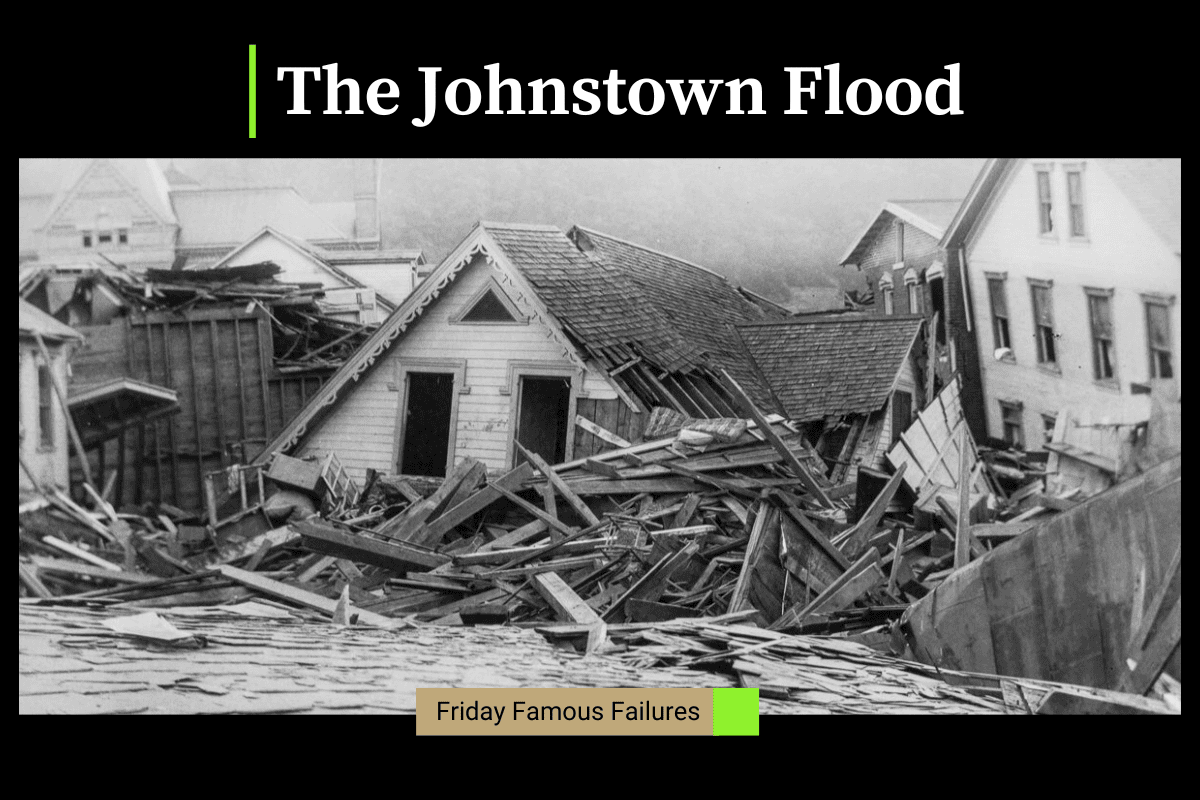

The rain pelted the men who desperately tried to save the dam, located 14 miles upstream of the town of Johnstown, PA in the southwest corner of the state. Hours earlier, Elian Unger, the president of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, woke to a swelling Lake Conemaugh. Overnight, heavy rainfall had created roaring surges out of creeks. Unger ran outside to assess the situation and could see that the water nearly crested above the South Fork Dam. He assembled a group of men to help save the face of the dam and to try to unclog the spillway. Twice, Unger ordered engineer, John Parke, to ride horseback to the nearby town of South Fork to the telegraph office to send the alarm to Johnstown. But Parke did not go himself; he sent another in his place. Tragically, the warnings were not passed to authorities in town as it was considered a false alarm. By 1:30 pm, the men trying to save the dam felt their efforts were futile; the men took to high ground, defeated, feeling all they could do was wait and watch the disaster. The rain continued to fall in Johnstown with water rising as high as 10 feet. Between 2:50 and 2:55 pm on May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam breached, sending 3.843 billion gallons of water roaring towards the town of Johnstown. The result was total destruction: 2,209 people perished, making it the largest loss of civilian life in the United States at the time.

How and why did the dam fail?

The aftermath of the dam breaking was catastrophic. Bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati and as late as 1911. According to records compiled by The Johnstown Area Heritage Associate, 99 entire families died in the flood, including 396 children. One-third of the dead, 777 people, were never identified and their remains were buried in the “Plot of the Unknown” in Grandview Cemetery in Westmont. The destruction caused $17 million in property damages, akin to $497 million in 2016.

The American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton and with 50 volunteers, undertook major disaster relief efforts. Support poured in from across the nation and 18 foreign countries.

Five days after the dam breach flood, the American Society of Civil Engineers spearheaded a committee of four engineers to investigate the cause of the disaster. The committee was led by James B. Francis, a hydraulic engineer best known for his work related to canals, turbine design, and dam construction and a founding member and former president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. The committee visited the South Fork Dam, reviewed the original engineering plans and modifications, interviewed eyewitnesses, and commissioned a topographic survey of the land. They resolved that the dam was bound to fail, and would have failed even if it had been maintained within the original design specifications, which included a higher embankment crest and five large discharge pipes at the dam’s base – before the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club made modifications to the dam. These findings have since been challenged.

In the years following the devastation, some blamed the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for the modifications to the dam and the failure to maintain it throughout the years. The law firm of Knox and Reed, whose partners were both club members, successfully defended the club. They argued that the failure was the result of a natural disaster that was an Act of God and no legal compensation was paid to the survivors of the flood. Nonetheless, individual members of the club contributed to the recovery and donated thousands of dollars to the relief effort in Johnstown. Andrew Carnegie, a known philanthropist, built the town a new library.

A hydraulic analysis published in 2016 confirmed what had long been suspected—that the changes made to the dam by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club severely reduced the ability of the dam to withstand major storms. Lowering the dam by as much as 0.9 meters (3 ft) and failing to replace the discharge pipes at the base of the dam cut the safe discharge capacity of the dam in half. This fatal lowering of the dam greatly reduced the capacity of the main spillway and virtually eliminated the action of an emergency spillway on the western abutment.

Survivors were unable to recover damages in court because the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club had ample resources and its members were some of the most powerful men in the United States. The wealthy club owners had also designed the club’s financial structure to separate their personal assets. Because of the torrent of rain and the report by the American Civil Society of Engineers, it was difficult to prove that the club owners had behaved in a negligent manner. The survivors’ inability to collect damages was widely reported in the press. As a result, state courts started to adopt Rylands v. Fletcher, a British common-law precedence that held that a non-negligent defendant could be held liable for damage caused by the unnatural use of land. Rylands foreshadowed the legal system’s 20th-century acceptance of strict liability.

Today, the Johnstown Historical Society now owns the Carnegie Library. The old library is now used as The Flood Museum which honors those who perished and tells the tale of this tragic disaster.

For those interested in additional detail, I suggest reading The Johnstown Flood

By David McCullough, copyright 1968. McCullough is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, meticulous researcher and gifted storyteller. It is available as an audio book on Audible and other sources and is narrated by the author.

I question the stated quantity of water.

“sending 3,843 billion gallons of water roaring”

I suspect a typo, that the correct quantity is more like 3.8 billion gallons.

In any case, the number is likely presented with too much accuracy (especially for an engineering article). I doubt the quantity could be known/calculated to 4 significant digits.

Thanks for correcting the article; good work.

The article uses a decimal point … not a comma.