This is the April 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

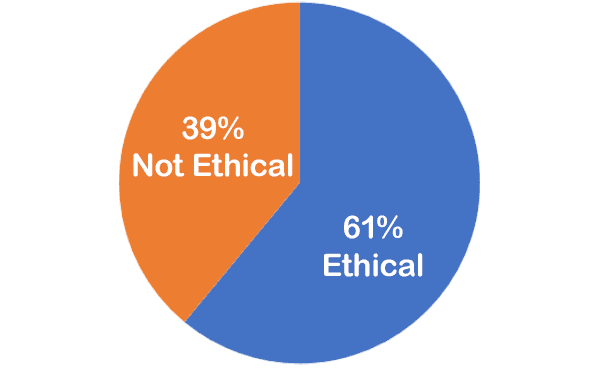

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the April 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on April 26.

Your opinion has been registered for the April 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on April 26.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Peter is retained by a major franchiser to provide engineering design services for a chain of stores throughout the United States. After several years, the franchiser decides to terminate its relationship with Peter and provides Peter with notice of its intent not to renew its contract with Peter’s firm. In order to maintain continuity and before the contract expires, the franchiser begins discussions with Engineer Bobby and retains Bobby to provide an immediate review of design concerns that are pending in connection with the design of several franchise facilities throughout the US. Prior to the review, the franchiser specifically tells Bobby not to disclose, to Peter, Bobby’s relationship with the franchiser. Nevertheless, Bobby reviews the design information the following week and, following his review, notifies Peter of his relationship with the franchiser and the preliminary results of his review. Several weeks later, Peter’s agreement with the franchiser expires, and the franchiser retains Bobby as its design engineer.

Was Bobby’s act of notifying Peter of his relationship with the franchiser consistent with the Code?

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code II.1.cEngineers shall not reveal facts, data, or information without the prior consent of the client or employer except as authorized or required by law or this Code.

Code II.4

Engineers shall act for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.

Code III.4

Engineers shall not disclose, without consent, confidential information concerning the business affairs or technical processes of any present or former client or employer, or public body on which they serve.

Code III.7.a

Engineers in private practice shall not review the work of another engineer for the same client, except with the knowledge of such engineer, or unless the connection of such engineer with the work has been terminated.

Discussion

One of the more challenging areas of engineering ethics issues involves the everyday relations among engineers. At one time, the Code had strict provisions regarding relations among engineers. However, with the passage of time, these strict provisions have been carefully modified to reflect the needs of clients and the evolving nature and realities of engineering practice.

As with any provision of the Code of Ethics, provisions regarding relations among engineers must be carefully balanced with the needs and requirements of the individual client as well as the particular facts and circumstances of the case. It is not always possible to draw fine distinctions in this area; however certain general ethical principles as enunciated in the Code of Ethics provide guidance in the resolution of these issues.

As has been noted on several occasions by the Board, the question of one engineer reviewing the work of another engineer has long been a subject of inquiry by the Board. Code III.7.a. admonishes engineers against reviewing the work of another engineer for the same client except with expressed knowledge of the engineer or unless the original relationship between the first engineer and the client has been terminated.

In BER Case 79-7, an engineer was asked to inspect mechanical and electrical engineering work performed seven years earlier. The Board concluded that the engineer notified the former engineer that the engineer was being retained to perform review and inspection services and that the review would entail a review of the original design. Said the Board: “It may be helpful for future guidance to again point out that the purpose of Code III.7.a. is to provide the engineer whose work is being reviewed by another engineer an opportunity to submit . . . comments or explanations for . . . technical decisions, thereby enabling the reviewing engineer to have the benefit of a fuller understanding of the technical considerations in the original design in framing comments or suggestions for the benefit of the client.” We believe the reasoning cited by the Board in BER Case 79-7 are as cogent today as they were when the Board issued its opinion.

At the same time, Code II.4 places the obligation upon engineers to act in professional matters for clients as “faithful agents or trustees.” An “agent” is generally defined as a “person authorized by another to act for him or one entrusted with another’s business.” A “trustee” is generally defined as one who stands in a fiduciary or confidential relationship to another. However, as noted in Black’s Law Dictionary (Fourth Edition):

“Trustee” is also used in a wide and perhaps inaccurate sense to denote that a person has the duty of carrying out a transaction, in which he and another person are interested, in such manner as will be most for the benefit of the latter, and not in such a way that he himself might be tempted, for the sake of his personal advantage, to neglect the interests of the other…”

Frankly, it is not clear from a plain reading of the Code whether the original drafters intended that the term “trustee” embrace the fiduciary and confidentiality relationship or whether it was the intent of the drafters to express a more general duty of loyalty and fair dealing. However, in view of the fact that drafters of the Code included separate provisions specifically addressing the obligations of engineers to not disclose confidential information (See Code II.1.c. and Code III.4, Code III.4.a., and Code III.4.b.), we interpret the term “trustee” to refer to the more general duty of loyalty and fair dealing.

The facts, in this case, present the Board with two conflicting provisions of the Code of Ethics: (1) the obligation of the engineer to provide appropriate notice to another engineer in connection with his reviewing the work of that engineer, and (2) the general duty of the engineer as “faithful agent and trustee.” In light of the facts and consistent with BER Case 79-7, we are persuaded that Bobby acted unethically in notifying Peter of Bobby’s relationship with the client. Bobby had an obligation not to notify Peter of his relationship with the client once he was told by the client not to disclose this information.

Finally, we are troubled by the fact that Bobby took this project without first exploring the reason why the client wanted Bobby not to disclose his relationship with the client. We believe this issue should first be clarified.

Our conclusion is based upon the rationale cited above in BER Case 79-7 but is also based upon an analysis of the countervailing argument that Bobby had an obligation as a “faithful agent and trustee” to not to tell Peter of his relationship with the client. As we noted earlier, the general duty of loyalty and fair dealing denotes that a person has the duty of carrying out a transaction, in which he and another person are interested, in such manner as will be most for the benefit of the latter, and not in such a way that he himself might be tempted, for the sake of his personal advantage, to neglect the interests of the other. A review of the facts, in this case, makes clear that Bobby did not appear to be motivated by personal advantage in informing Peter of his relationship with the client. We surmise that Bobby’s disclosure of his relationship with the client constitutes neglect of the interests of his client, and we believe that on balance that the benefits to be derived by Bobby’s disclosure for all parties involved did not outweigh detriments that may be suffered by the client.

Finally, in passing, we would note that Bobby’s delay in informing Peter of his relationship with the client and the preliminary results of his review was not a violation of Code III.7.a. We interpret Code III.7.a. to require disclosure within a reasonable period of time following the establishment of the relationship and the review. We find nothing to suggest that Peter’s rights were prejudiced by the short delay. In view of all of the facts and circumstances involved in this case, we believe the one-week delay is not unreasonable and consistent with Code III.7.a.

It should be noted that the Board was split on whether it was ethical for Bobby to proceed with the review and could not reach an agreement.

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

Bobby’s act of notifying Peter of his relationship with the franchiser was not consistent with the Code.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

Donald L. Hiatte, P.E. William W. Middleton, P.E. Robert L. Nichols, P.E. William E. Norris, P.E. William F. Rauch, Jr., P.E. Jimmy H. Smith, P.E. William A. Cox, Jr., P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

The specific language of Bobby’s agreement could impact the outcome. If the written agreement stated no disclosure outside the company inclusive of former employees and consultants, it could have been clearer regarding Bobby’s ethical/nonethical behavior.

1. Bobby should have not disclosed his relationship with Franchiser to Peter. He was requested not to do so by his client; client would have every right to cancel contract with Bobby as result of this.

2. Bobby certainly should not have communicated with Peter in any way, shape or form without approval of Franchiser.

2. Code Code III.7.a could be and should be legally challenged in court as improper restraint on an entity to have an engineer’s work reviewed independently by another engineer.

It is a delicate case but following the Code III.7.a governs all other code points since it was done in the legal Code time frame given that the relationship with Peters was not terminated till after the review of the other engineer.

In reading the facts, I don’t know why the client decided to switch engineers. I inferred from the facts that they were not happy with Peter’s designs and were actually concerned with the product. I thought it was acceptable and required for Bobby to bring design flaws (my assumption) to Peter’s attention. Thus i thought it was ethical.

Codes II.1, II.4 and III.4 do not specifically name “another engineer” among the parties information should not be disclosed to.

Code III.7.a specifically addresses “another engineer” so it trumps the other Codes as a requirement to be notified while the other engineer is still connected with the work which it applies to this specific case.

I see nothing wrong with a client wanting a confidential “second opinion” and, therefore, asked the engr. Not to disclose his relationship. The work of the other Engineer was “done”. Consulting with the other engineer is not in line with an “objective Second Opinion not tainted by another engineer”. As a forensic engineer reviewing engr. work performed years ago, I would never inform the other engineer due to the confidentiality of the attny engr. relationship especially on the front end of the job to explore liability. So, the only diff between my work and this case is the passage of time. I would not have notified the other engr. I was doing additional design review because I would have agreed to Confidentiality per se. gregory a. harrison, Phd., P.E.

I think the root of the problem was that Bobby took on a project that would require him to do something that was not ethical. Any of his next actions then involved trying to make the least worst unethical decision.

What if the client owed Peter money? What was the reason for the split. Perhaps the client wanted Peter to do something that was unethical and Peter refused. Bobby did the right thing in talking to Peter.

I believe the error here is when the Client asked Bobby to review Peter’s work without informing him, that Bobby should have explained to the Owner that the Professional Code of Ethics would not allow him to review the work without informing Peter of his relationship with the owner and his task to review Peter’s work. This most likely would lead to a discussion of he reasons why the Client wanted to keep this secret from Peter or a denial of work to Bobby. Bobby should be aware that if the Client is doing this to Peter, will the same thing happen to Bobby at a later date?

It seems to me that the “agent” obligation is not as binding as that of letting an engineer know that his work is under review. What if the firm asked an engineer, as it’s “agent,” to do something unethical or illegal? I believe that the answer is clear if the request is illegal, but I think that the same argument holds in either case. Maybe Bobby was unethical, not in informing Peter, but in accepting the firm’s condition that he not tell Peter something that he was ethnically bound to tell.

I believe that if Bobby found something wrong that would potentially jeopardize the public, Code I. 1. would trump the Board’s findings. I think Bobby found something serious enough to call Peter.

If you didn’t want to abide by your clients request, then do not accept the project.

There is probably a biased decision centered on the age of the responders. It would be interesting to know how the younger engineers would see this when compared to older engineers. I say this because there has been a relaxation in the ethics parameters in recent years.

My ambivalence on this issue is due to a lack of clarify on what I believe is a critical point. Who owned the design being reviewed? If Engineer Peter was and remained the engineer of record for the design in question, then disclosure is appropriate and, in my opinion, required. If Engineer Bobby was assuming ownership as engineer of record, then an argument could be made that disclosure would not be necessary.

I am not a lawyer … thank goodness. Speaking engineer to engineer you should be able to tell the truth, and, hopefully not have to worry about some lawyer twisting your words around to make a buck.

Section III.7.a trumps all other considerations, especially as the contract relationship between the franchiser and Peter is still in force. How are people not seeing this? Reviewing the work of another engineer is ripe for the formation of an adversarial relationship and accusations of misconduct by Peter against Bobby if the disclosure is not made. Specific concerns of the client regarding the designs can’t be reviewed “in vaccuo” by Bobby. He would need an understanding of the decision process. It could very well turn out that the areas of “concern” were created by underlying requirements from the client which they might otherwise “forget” to mention to Bobby in the course of his analysis.

I don’t think there are enough details given, to support many of the comments offered. I agree with one of the first comments, that the “client would have every right to cancel their contract with Bobby as a result of this.” However, I think that any ethical question here ultimately falls on the precedent that an engineer, above all other considerations, and “without reservation” should act “for the public good.”

I disagree with the last paragraph of the explanation article.

Peter should have been informed before the review, and given the opportunity to explain or provide additional information concerning design decisions to Bobby.

While Peter is still under contract, he is obligated to continue providing professional services, even when aware that his contract will end, and a new engineer is now (or will be) under contract. Yes there may be hard feelings. but Peter must remain professional and serve his client’s interest. The client should not have asked Bobby to keep his intentions secret.

Very interesting case. I would have liked more details, as I can see other things impacting this. What if Bobby found a major design issue? Why didn’t Bobby tell the client that per the code of Ethics he needed to talk to Peter? What type of design concerns did the client have?

I personal leaned towards the III.7.a part feeling that for a professional engineer that type of communication was by far the most important and had a tendency to impact the public good more. Generally when a client asks you to keep something secret, it makes me nervous. (Thought there are very good reasons in some cases.)

If the short, one-week, delay in notifying Peter was not unreasonable, did not prejudice Peter’s rights, and is considered consistent with Code III.7.a, then a several week delay in terminating Peter’s contract should also have the same non-effect on that portion of the Code. Therefore, the last part of III.7.a., “. . . or unless the connection of such engineer with the work has been terminated.” is apropos. Therefore, III.7.a may be considered as non-applicable.

Code should be updated to conform all sections.