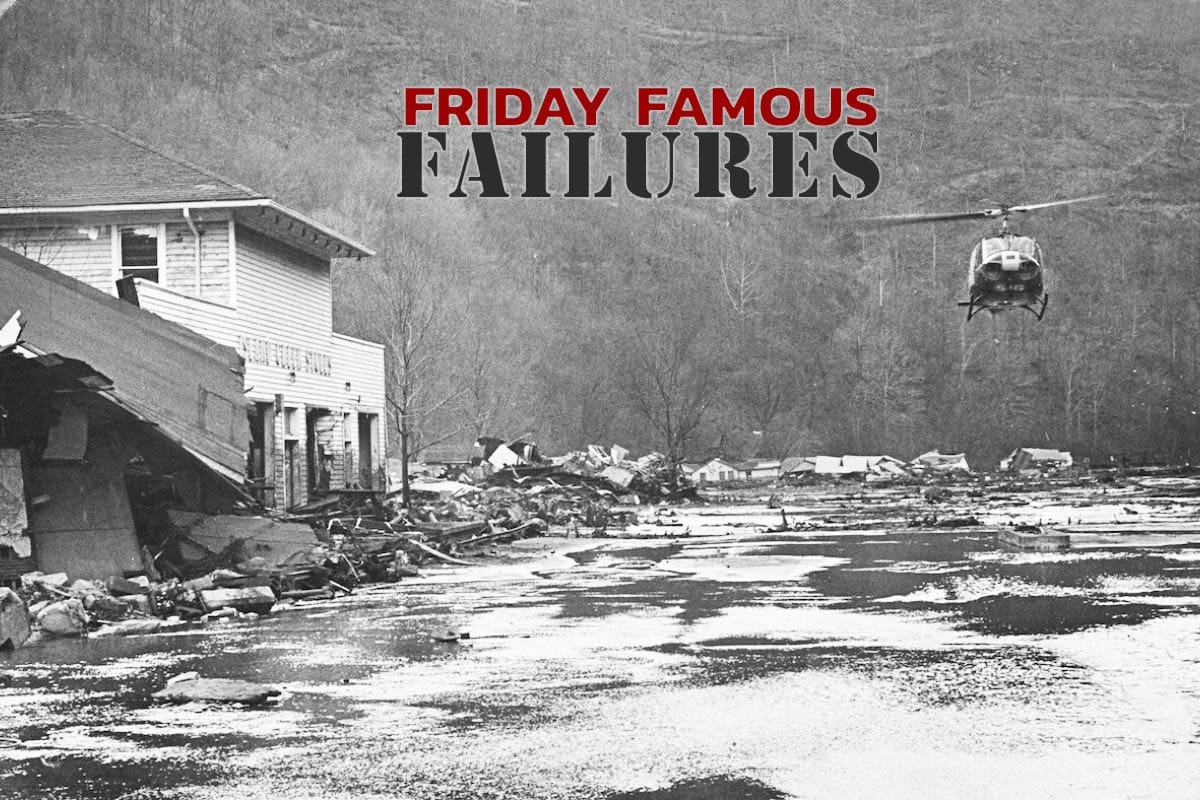

On the days preceding February 26, 1972, Buffalo mining officials kept an eye on a local coal refuse dam in Logan County, West Virginia, as heavy rain continuously fell. The company measured water levels every two hours over the night of the 25th, and alerted officials in the nearby communities of the increased risk of flooding. However, when two sheriff’s deputies arrived to help with evacuations, the company sent them away; none of the local inhabitants were warned. Yet despite the lack of information, some residents sensed the danger and moved to higher ground.

At 8:00 a.m. on February 26, heavy equipment operator Denny Gibson noticed that the water had risen and the dam was “real soggy.” Just five minutes later the dam collapsed and approximately 132 million gallons of black wastewater rushed through Buffalo Creek hollow. In a matter of minutes, 125 people were dead, 1,100 injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless.

What caused this disaster?

The Buffalo Mining Company operated five underground mines, a strip mine, and two auger mines near Buffalo Creek in West Virginia. All of the coal from the mines was processed through a central preparation plant. The plant operated two shifts, five or six days a week. The plant processed about 5,200 tons of run-of-mine (raw) coal a day, which generated 1,000 tons of refuse. The refuse was removed from the raw product and transported to a storage bank. Much of the refuse was then used to make retaining dams for the processing plant’s wastewater. Between 1964 and 1970, three retaining dams were constructed.

In the week prior to the dam failure, Logan County experienced heavy rainfall; over the five preceding days, 3.84 inches of rain were estimated. This amount of water was augmented by snow melted by the rain and joining the runoff. During this period, all the mines on Buffalo Creek were active and generating wastewater. A coal mine inspector and a company safety engineer inspected the refuse bank and retaining dams three days prior to the collapse, on February 22, and deemed them to be in satisfactory condition. The inspector noted at the time that the wastewater was roughly 15 feet below the top of the upper dam. Nevertheless, a superintendent of the company’s stripping operations continued observation of water levels. By late afternoon on February 25th, the superintendent was concerned enough to visit the dam at two-hour intervals. Many other people were concerned as well, and afterward noted they had regularly checked on the dam leading up to its collapse. Yet, not one actually witnessed the failure of the upper dam. Many did, however, report hearing explosions when the water reached the refuse bank which was still partially burning from the coal processing operation.

Two commissions investigated the disaster to determine the cause and responsible parties. The first, the Governor’s Ad Hoc Commission of Inquiry was appointed by then-Governor Arch Moore, Jr. and was extremely sympathetic to the mining company. When the United Mine Workers asked to have a coal miner be added to the commission, the Governor refused. Then, a separate citizen’s commission was formed to provide an independent review. After investigation, the Governor’s Commission found no serious fault in any actors and called for new legislation to prevent future dam collapses. The citizens’ commission report, however, concluded that Pittston Coal Company was guilty of murdering at least 124 people because of their blatant disregard for standard safety practices.

The third dam, built behind and above the previous two dams, rested on a bed of coal silt and sediment that settled from the wastewater and remained on the bed of the reservoirs behind the second dam. This was an inadequate foundation for the dam, though it would have been more difficult and expensive to clear the sediment before constructing the third dam. The flood began when dam three failed, then the water from its reservoir overwhelmed and destroyed dams one and two.

In testimony before the Ad Hoc Commission, Mr. D.S. Dasovich, V.P. of Buffalo Mining Company, stated that the method of constructing Dam No. 3 “. . . is common practice throughout the coalmining regions.” No engineering plans were ever made for the construction of the impoundment. The only plan was Mr. Dasovich’s sketch made on February 26, 1968. Mr. Dasovich stated in reference to the design of Dam No. 3, “I wouldn’t even begin to be able to engineer a thing like that. It has no . . . I know of no formula or any such method of so-called designing it.”

The citizen’s commission pointed out the flaw in dam three as the cause of the disaster, holding the company responsible for the disaster. Additionally, the chair of the citizen’s commission called for the legislature to outlaw coal strip mining, which he claimed as a potential cause of the disaster due to the creation of so much refuse and wastewater. Pittston officials rejected these conclusions but offered no alternative fact-based explanation, calling the flood an “Act of God” and saying the dam was simply “incapable of holding the water God poured into it.”

A circuit court grand jury failed to return any indictments against Pittston despite the alleged violations. In May 1972, Governor Arch Moore, as he ran for a re-election campaign, proposed ten redevelopment projects for Buffalo Creek that would aid victims of the flood. Few of these developments were completed on time and most never materialized. Instead, the Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development set up temporary mobile home communities for those left homeless from the dam collapse. Of the 750 projected public housing units, only 17 model homes and 90 apartments were ever built.

The disaster at Buffalo Creek reawakened the Mine Health and Safety Administration to the importance of enforcing federal regulations. At the state level, the West Virginia Legislature passed the Dam Control Act, providing oversight and regulation of all dams in the state, but funding was never allocated to enforce the law.

Numerous lawsuits were filed in response to the disaster. In the largest class-action suit, 600 survivors and family members of victims sued Pittston for $64 million. The plaintiffs settled out of court in 1974 for $13.5 million; each individual received an average of $13,000 after legal costs. Lawyers for the plaintiffs from the firm Arnold & Porter of Washington, D.C., donated a portion of their legal fees toward the construction of a new community center. The state never built the promised center.

Has there been any change since that require Engineering Certification of these types of “dams”. Obviously strip mining is still practiced. What keeps this from happening again?

It is a shame that political favors can run so favorably against the public they are supposed to serve. It appears no matter how much concern for safe engineering is demanded, a few dollars and greed can overcome the public interest. True justice from our governing body is too deeply dependent upon corporate money. Far too many corporations have no conscience.

Money corrupts politicians.

Lawyers make too much money for the good they provide to society.

Lawyers are just junior politicians.

This is an example of those tragic lessons learned and why we engineers have to be more assertive when voicing our concerns.

Attorneys, politicians, mining company wins and victims lose. Very sad….but not surprising.

Am a retired civil engineer with some half century experience in design calculations, for low head rock, earth and timber crib type dams. Also HUD type flood studies in the 1970s. Many of the 19th Century industrial mining tailing pond type impoundments were constructed by approximate, “rule of thumb design” methods, usually with no hydrologic nor hydraulic analysis, and very little foundation investigations. This was the case with many early canal feeder dams also.

No studies noted that shared any data regarding how much rainfall was allowed to occur before problems ensued. No statement that an emergency spillway was constructed. No loading calculations were done on the dam’s stability based on its fluidity of materials.

An unbelievable situation. Mine owners, company representatives should have been jailed. This could have been avoided.

Just like the refinery accidents in Texas, this is just ‘doin’ bidness’. Engineers are POLITICAL IGNORAMUSES because they believe that THEY alone can stand up for safety. OK guys, here is the deal:

A man named Goedel earned a Nobel Prize for mathematics for his incompleteness theorem and his undecideability corollaries. In his work, Goedel pointed out that the herd always triumphs over the individual because the herd knowledge (read political correctness) exceeds the individual brilliance. Herein is a simple example. Watson, the IBM computer, crushed its human opponents in the game of Jeopardy. Well, I can find some folks who can whip Watson mercilessly tomorrow. It turns out that there are about 300 non-written languages – Navajo, Hopi, and Ojibaway – among them. If Jeopardy is conducted in these languages, Watson has no hope of winning. The languages are passed down to each generation Orally, and Watson has not been trained in any of these languages – Watson has no chance. Similarly, UNLESS engineers start organizing (good gosh almighty ) the way Lawyers and Doctors organize to protect their professional interests – that is get laws passed that FORCE legislators, bureaucrats, corporate CEO’s and other political miscreants to acquiesce to the ENGINEERING PROFESSION”S standards. Until WE as a profession start acting as a group, these types of tragedies will continue to occur irrespective of any laws that are present, past, or future (By the way, Godel’s incompleteness theorem clearly proves that any set of laws will have loopholes and/or contradicitons)

As a retired civil engineer who recently purchased a summer home in WNC, I am now finding the same lack of awareness, capability, or involvement on behalf of the public trust, by the governmental agencies appointed to guard against malfeasance by land owners and developers who ignore the codes and do what they will, in spite of their charges’ best efforts to prevent loss of life and property.

This wasn’t an engineering problem, though engineering analysis is certainly a tool to diagnose what happened technically. What was needed was real root cause analysis and that goes beyond engineering into the political, social and governmental spectrum. And that isn’t going to happen anytime soon in our culture

As a result in our case, our property association has to pay to recreate an impoundment to control upstream runoff from running through one of our residents’ home and polluting an important water source for our end of the county! And realtors don’t help matters in a buyer beware market such as real estate. The one who caused this problem is now long gone along with the realtor who convinced him to fill in the pond to make more money.

This was a terrible disaster that occurred ~48 yrs ago. I would like to think that regulations have become more stringent and coal mining companies have improved their operations such that it could never happen again. However, I have heard of environmental disasters (not sure about loss of human life) occurring a number of times in West Virginia since then.

I don’t know if coal mining can ever be safe or clean and still be financially feasible. It just makes me hope all the more for the success of alternative energy sources in the very near future.

Local authorities allowed the construction of the dams to happen

without questioning their design. It is the easy way out to ignore it instead of raising their voice. Someone should have gone to prison for not doing their job.

Stability study of the dam needs to be documented for maximum loading before construction by considering the geotechnical properties of the used construction material.

The question in of itself is flawed, just because you have formal training and a degree hanging on the wall doesn’t mean you are good at what you do. Unlike many who just jump into continued education right after high school I was fortunate to not take that route. When I graduated high school there was very little in area of student financing and chose to work and save before heading off to get a degree. What this did was give me allot of year of hands on in the field experience.

I did not spend very many years in civil engineering, the of incompetence was beyond belief at times. I returned to my roots as a Construction Superintendent which was far more lucrative. I recently finished a road widening project through very hilly terrain and the engineering was such that we were to not remove any top soil and or duff before starting the fill and compaction. We put up a fight on this requirement and gave in because our bonding for the project had threatened by local Gov’t officials. We did however get everything in writing removing all liability from us if the subsequent road widening experienced a failure.

After 2 days of continuous light saturating rain a section of the road widening had started to move down the hill. All lengthy court battle ensued to which we were successful in winning not just from the waiver of liability but having an independent engineering firm revue the design and specifications it was agreed that the original design was flawed and should not have been allowed to proceed.

The local Gov’t officials wouldn’t have ever considered questioning their preferred engineering firm due too a basic lack of knowledge and I am sure the amount of gifts they had received over the years had nothing to do with it at all.