This is the March 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think? This series is comprised of case studies from NSPE archives, involving both real and hypothetical matters submitted by engineers, public officials and members of the public.

Your peers and the NSPE Board of Ethical Review have reviewed the facts of the case as shown below. And, here are the results.

Your opinion has been registered for the March 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on March 22.

Your opinion has been registered for the Match 2022 edition of our monthly series of Ethics case studies titled What Do You Think?

Your vote is recorded as:

Want to know how your peers voted? We’ll send you an email with the poll results on March 22.

A Review of the Facts

Engineer Wally, a registered professional engineer, has worked on the design and development of improved wastewater treatment processes and equipment, which were subsequently patented. Engineer Theodore, an environmental consultant specializing in the design of wastewater treatment facilities, and his client, are impressed with the new processes and equipment. However, Theodore dislikes specifying the sole source and, in fact, makes a point of encouraging competition by preparing open specifications with “or equal” clauses or by specifying a performance requirement. The primary, if not the sole, purpose of Theodore’s effort is to minimize cost by promoting competition. On this project, Theodore prepares a performance specification for open competition but patterned from the performance of the processes and equipment patented by Wally.

Was it ethical for Theodore to use Wally’s patented processes and equipment as a guide in preparing open specifications in order to minimize cost and to promote competition?

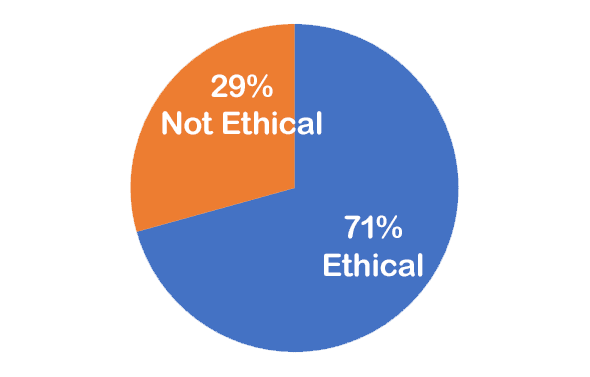

Here is the result of our survey of your peers:

Applicable NSPE Code References:

Code II.4

Engineers shall act in professional matters for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees.

Code III.5.a

Engineers shall not accept financial or other considerations, including free engineering designs, from material or equipment suppliers for specifying their product.

Code III.7.c

Engineers in sales or industrial employ are entitled to make engineering comparisons of represented products with products of other suppliers.

Code III.9

Engineers shall give credit for engineering work to those to whom credit is due, and will recognize the proprietary interests of others.

Code III.11

Engineers shall cooperate in extending the effectiveness of the profession by interchanging information and experience with other engineers and students, and will endeavor to provide opportunity for the professional development and advancement of engineers under their supervision. (This language no longer exists in the current NSPE Code of Ethics)

Discussion

There is concern expressed within engineering circles that the number of U.S. patents being filed by U.S. manufacturers has been declining. As noted by the president of a leading patent, trademark and copyright association, “fewer than half of U.S. patents issued will be going to U.S. inventors, and the American economy will be the big loser.” One alleged reason for the decline is the increase in “copycat” versions of products and processes being manufactured. One engineer noted that while a “better mousetrap” is terrific, the more competitively priced “copycat” versions discourage or eliminate those firms that made the investment in creating a “better mousetrap” by preventing them from recouping their original costs.

It would seem that the fundamental issue involved in this case is whether and to what extent one engineer has an ethical responsibility not to encourage others to develop alternatives based upon the technical ideas and developments of another engineer.

The Board of Ethical Review has never squarely addressed the question raised by the facts in this case. However, as early as BER Case 64-7, the Board noted that individual accomplishments and the assumption of responsibility by individual engineers should be recognized by other engineers. “This principle,” said the Board, “is not only fair and in the best interests of the profession, but it also recognizes that the professional engineer must assume personal responsibility for decisions and actions.” While BER Case 64-7 reflected the basic view that each individual engineer has an ethical obligation to recognize and give credit to the creative products of other engineers, the case did not address the question of one engineer’s ethical responsibility not to persuade manufacturers to produce optional devices using the concepts of another engineer.

Over the years, the two cases that have probably come closest to addressing these issues, however remotely, are BER Cases 77-5 and 83-3. In BER Case 77-5, an engineering firm submitted a project study originally prepared for a federal client to a state agency to assist the agency in obtaining funding for a project. After obtaining the funding, the agency distributed the study to another engineering firm that used the contents of the study as part of its negotiations with the state agency. In concluding that it was ethical for the second firm to enter into negotiations for the project under the circumstances, the Board could not find any specific provisions of the Code which dealt either directly or indirectly with the obligations of an engineer on behalf of or as an agent of the owner to avoid taking advantage of another engineer who had in good faith provided substantial and valuable information for a proposed project on the understanding that the engineer providing the assistance would receive the commission for it. The Board, deploring the lack of specificity in the Code, suggested that consideration be given to an appropriate revision or addition to the Code to cover such a situation. Said the Board, “our reluctant conclusion may meanwhile serve the purpose of alerting engineers in private practice who are tempted to expend substantial time, effort, and funds to secure a commission to the danger they run when that investment exceeds a nominal investment.”

Following the rendering of BER Case 77-5, the National Society of Professional Engineers Board of Directors took steps to modify the provisions of then Code 11 of the Code of Ethics. However, instead of strengthening Code 11 as recommended by the Board of Ethical Review, the Board of Directors deleted several provisions of that section in order to comply with the federal antitrust laws. An abridged version of Code 11 ultimately became the current Code III.7 contained in the Code of Ethics.

Later, in BER Case 83-3, which involved facts similar to BER Case 77-5, the Board concluded that it was unethical for one engineer to use the data of another engineer to develop a proposal submitted to a public authority without consent.

It is clear under the facts of the present case that Wally has devoted a great deal of time, effort, and creativity to the development of the improved wastewater treatment processes and equipment. The fact that Wally’s achievements have been granted patents is a clear demonstration of the quality and distinction to which his work has been recognized. It may seem to some that, in fairness, Wally would be entitled to exclusive control over the fruits of his creative work and that competitors would be excluded from using the concepts and theories behind his creations to develop alternative processes and equipment that might achieve the same or similar result. However, we believe that such a notion would be inconsistent with basic principles of law as well as the philosophy expressed in the Code of Ethics Code III.11, which obligates engineers to cooperate in extending the effectiveness of the profession by interchanging information and experience with other engineers…” (Note that Code III.11 was removed from the Code subsequent to the Board’s ruling on this case.)

It should be noted that a fundamentally accepted principle is that an “idea,” “thought,” “notion,” or similar abstraction cannot receive legal or other proprietary protection under the law. Rather, it is the expression of that idea, thought, or notion that can receive appropriate legal protection. This view is grounded in the philosophy that in order to best promote scientific and technological advances within our society, individuals and groups of individuals should be free to use ideas and concepts to develop different expressions of those ideas without legal hindrance. It is consistent with the principles of total quality management, including the goal of constant improvement in the design process.

We believe that this basic philosophy is applicable in this case. Theodore did not seek to infringe upon the patent of Wally. Instead, it appears that under the facts, Theodore merely used the processes and equipment developed by Wally as a “standard” by which different processes and equipment would be evaluated or, as an alternative, established a performance specification based on the performance of Wally’s processes and equipment which would be used to evaluate the performance of different processes and equipment.

As to the question of the primary or sole purpose of Theodore’s efforts (minimizing cost to the client by promoting competition among suppliers), we believe such an objective is entirely consistent with the engineer’s general obligation to the client to act as faithful agents or trustees (Code II.4).

The Ethical Review Board’s Conclusion

It was ethical for Theodore to use Wally’s patented processes and equipment as a guide in preparing performance or open specifications.

BOARD OF ETHICAL REVIEW

William A. Cox, Jr., P.E.; William W. Middleton, P.E.; William E. Norris, P.E.; William F. Rauch, Jr., P.E.; Jimmy H. Smith, P.E.; Otto A. Tennant, P.E.; Robert L. Nichols, P.E., Chairman

Note – In regard to the question of application of the Code to corporations vis-a-vis real persons, business form or type should not negate nor influence conformance of individuals to the Code. The Code deals with professional services, which services must be performed by real persons. Real persons in turn establish and implement policies within business structures. The Code is clearly written to apply to the Engineer and it is incumbent on a member of NSPE to endeavor to live up to its provisions. This applies to all pertinent sections of the Code. This opinion is based on data submitted to the Board of Ethical Review and does not necessarily represent all of the pertinent facts when applied to a specific case. This opinion is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as expressing any opinion on the ethics of specific individuals. This opinion may be reprinted without further permission, provided that this statement is included before or after the text of the case.

So why bother patenting anything? Investment in the development of intellectual property is a waste of time?

Ethical, but pointless. Very unlikely to generate meaningful competition for an “or equal” when the process is patented. Better approach would be to negotiate the price if purchasing ordinance allows then assign the agreement to the installing contractor.

I agree with interpretations expressed by the Board (of Ethical Review). Should a vendor submit a response based on patented work, a license would have to be obtained from the patent holder. However, it has long been the case within patent law that even a slight “improvement” to a patented invention would allow for a patenting of the “improved” invention by the improver. Also, although a patent has been granted, it may be contested upon submission of facts that indicate that the patented invention does not actually meet the standard for granting a patent.

But basically, in this specific case as stated, Theodore is not specifying use of Wally’s patented process, but establishing performance (final results) of process as the baseline for evaluating submitted proposals. This is not a violation of patent law.

This was a very good case because hits the ‘gray area’ that many of us encounter in our working lives. It is clear that even the Board is not entirely clear on what is ethical. Bringing up the copycat issue is an important reminder about what happens in real life when you spend the money to get a patent. Unfortunately the cost of international patents is prohibitive for many small players, from whom many of the best ideas originate. There is no easy solution to this issue.

The Public benefits from an Engineer who writes Specifications that reflect the State of the Art and Best Practices in technology. The Public also benefits if competitively bid contracts result in the lowest cost for technology. There is nothing in the description of this case that would preclude competitors from licensing patented technology from the patent holder in order to develop competing systems and equipment. Thus the value of the patent holder’s intellectual property is protected. Advances in technology should be embraced when it benefits the Public. Engineer Theodore was Ethical in preparing open Specifications.

Thanks for the reference to Leave It To Beaver – many happy memories.

It can be assumed that Wally’s patented idea has merit and is, therefore, more efficient. If alternate designs can achieve similar performance without violating the patent, Wally’s ideas may be good but not substantial improvements. However, if Wally’s design is significantly better and alternate designs can not approach the performance then Wally’s design will need to be appropriately implemented to meet the performance criteria.

It doesn’t seem like this is a question of ethics but rather how good Wally’s design is. If the performance is substantially better, then using his performance criteria effectively demands that his design be appropriately incorporated into the current and future projects.

I believe Theodore’s actions would be ethical if Theodore used the patented performance standards as the basis of the Request for Proposals. I don’t believe Theodore would be ethical using Wally’s processes as the basis of an “or equal” system.

While this may be “ethical” in the most narrow possible interpretation of the word, it is really a very underhanded move to attempt to gain the benefit of Wally’s work without payment. Secondly, over my years, I have seen the “or equal” result in disaster on several occasions. What “or equal” turns out to mean is, “use the cheapest method and material that I can foist off on the client”. The quality of the resultant work is more dependent upon the salemanship of the contractor and the gullibility of the client than upon any real equivalence in quality of product, and his been without exception that I can recall resulted in lower quality finished product. I refuse to write an “or equal” clause. If you do not know enough about the results you want to write a clear specification for the materials and qualities of the finished product and have them based on tested and proven data rather than producers claims, you should not be developing the specification.

Having had a situation very similar to this with the generation of RO water for a paint shop, I could not and would not give the specifications or designs from one supplier to another. It does not promote competition, but instead makes you the “bad guy” for sharing details of another bidder’s design. If the other bidders have ways to accomplish the same end results, then bring it on. But they must prove their product is as good or better than of the original.

Theodore’s actions may have met the letter but not the spirit of the ethics rules. He was under the ethical obligation to disclose that a patented system could meet the requirements, but any use of such patented system would require the proper approval of and remuneration to the patent holder. This would alert potential submitters of the basis for the performance specification.

Maintain proprietary information as confidential to every extent possible when applying for a patent. But definitely do apply. You can bet foreign competitors apply for patents in order to penetrate the US/EU/UK markets. Stealing designs and proprietary information is big business, one that involves foreign agents at all levels, even interns. Competition among vendors is something we maintain out of fairness and a sense of fostering innovation in production. Where it takes a wrong turn is when the ability to protect innovation gets sacrificed for short term gain. That’s not what the engineer in this case was doing. Patenting a process allows you to license it for a specific period. His single source may entertain licensing offers so others can sell the product in a US market, for example. However, a slightly different process may produce better results and not violate the patent rights if it is indeed different. By setting the spec for a performance goal and saying “or equal” is allowing legal competition, not impeding it.

Also, if the process is patented, then the patent has published and is available free to read and study on uspto.gov. Anyone can read about the process, the ‘best mode’ to practice it, what is claimed and what is not claimed, and then honestly seek to invent a different process that performs even better or is less expensive. That’s how the patent process spurs continual improvements.

With regard to “why patent anything”? I would reply because Engineer Wally, with a patent, can sue any other firm using his idea that results from ‘patent infringement. Simply stated, If I develop a widget that reduces corner loads, anyone who uses the widget or makes the widget owes me royalties, whereas, a company that uses a ‘blivet’ to the the same job can sell their blivets. The PROVISO here is that no one can call a widget a Blivet and then sell the blivet. Unfortunately, the professional societies have been impotent when it comes to protecting intellectual property.