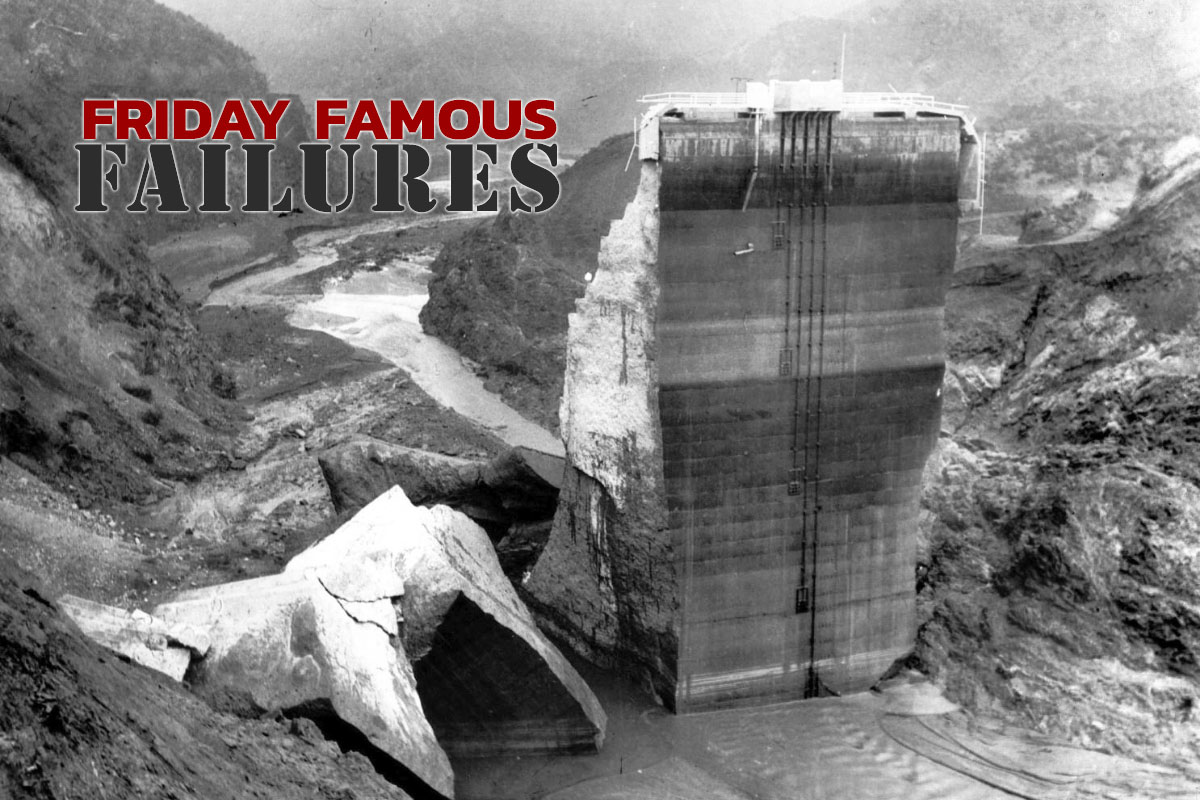

Just before midnight on a cool, moonless night in March 1928, the St. Francis Dam collapsed, sending 13 billion gallons of water in the form of a ten-story high torrent crashing along the Santa Clara riverbed towards the ocean. It would take 5½ hours to get there, but no official warning would be sounded for considerably more than an hour after the rupture. The devastation was overwhelming. It was one of the worst civil engineering disasters in U.S. history.

Because the collapse occurred around midnight, most people were in their beds sleeping. Ray Rising, an employee of the Department of Power and Water, lived near the dam with his family. Startled awake by what he described as a roar, Rising scrambled to get his family to safety. Rising’s entire house disintegrated. To survive, he held on to electric wires and hopped from roof to roof.

The official death toll from the disaster was 450, but many believe it claimed dozens of additional lives. The areas in the path of destruction were home to many Spanish-speaking migrant workers. These migrant workers did not leave their homes because the language barrier prevented them from understanding the warnings. In all, an estimated 900 homes were destroyed, and an additional 1200 homes were damaged. Dead bodies were found in the Pacific, some as far away as San Diego.

What caused this disaster?

Built by William Mulholland, known as the father of Los Angeles’ municipal water system, St. Francis Dam held more than a year’s supply of water for the entire city. As the city of Los Angeles was predicted to grow, Mulholland knew that the city needed a way to pipe in fresh water. Mulholland was a self-taught engineer who had no formal training; however, his dynamic accomplishments made him somewhat of a titanic figure. He was the first to use hydroelectric power construction and caterpillar tractors, and he was innovative in the design and construction of high earth dams. Throughout his younger years, Mulholland worked a variety of odd jobs across the U.S. Eventually, he secured a job as a ditch tender for the privately-owned Los Angeles Water Company (LAWC).

While at the LAWC, Mulholland made friends with Fred Eaton, the Chief Superintendent of the Water Company. When Eaton moved on to become the L.A. City Engineer and then later the mayor of Los Angeles, Mulholland assumed Eaton’s role as the Chief Superintendent. And it was in that role that he and Eaton devised a plan to ferry fresh water from the north and east of Los Angeles. This water would then travel hundreds of miles via a system of dams and aqueducts.

This project was not without controversy. Eaton purchased huge swaths of land where the aqueduct would be built and then sold them back to the city of Los Angeles for a large profit. Eaton also duped Owens Valley farmers. The U.S. Reclamation Service had a proposed irrigation project in the Owens Valley that would stand in the way of the L.A. aqueduct. Eaton impersonated a government official and met with farmers and convinced them to sign over their water rights to what they believed would be the Owens Valley irrigation project. Mulholland received death threats from Owen Valley citizens, and the L.A. Aqueduct was dynamited near the Alabama gate spillway. Because of the tension, Mulholland realized the need to develop new reservoirs outside Owen Valley.

The site selected was hundreds of miles away, and the canyon was located next to Powerhouse Number 2, which reduced the cost to generate hydroelectric power. According to Mulholland, the site had ideal topography for a large storage reservoir and could be acquired at a reasonable coast to the city. The dam was to be the largest concrete-arched gravity dam in the world. The original plans called for a 500-foot radius with a height of 175 feet above the streambed and maximum base width of 141 feet. However, shortly before construction began in 1924, Mulholland raised the dam 10 feet and increased the capacity of the reservoir to 32,000 acre-feet. Minor changes were made to accommodate the change, but the base width was not increased. Halfway through completion in 1924, Mulholland raised the dam another 10 feet and again did not increase the base width.

By 1928, the reservoir was filled to just three inches below the crest of the spillway, and the problems were immediate. Dam keeper Tony Harnischefer observed and reported leaks. Motorists traveling along the east shore complained of sagging roads.

On the morning of March 12, 1928, Harnsicher discovered a larger leak and called in Mulholland and his assistant Harvey Van Norma. For nearly two hours, the men observed the leak and determined it posed no threat. Mulholland acknowledged that corrective measures were required, but proposed they address repairs at a later date. Twelve hours later, disaster struck.

Days later, the Coroner’s Inquest began. One initial theory for the dam’s failure was sabotage, but there was no physical evidence to support this claim. Instead, the report found that errors in engineering judgment, as well as a disregard for public safety, caused the disaster.

Mulholland ignored the geography of the site. During the investigation, the subsoil of the dam was inspected; the east side had layers of mica schist and was exceedingly rough, whereas the west side had a high unstable red sespe conglomerate, which has a tendency to disintegrate in water. Mulholland had not consulted with geologists on the selection of the site, but geological opinion was not required for dam sites at the time.

Mulholland’s lack of formal engineering training affected his judgment. A modern-day analysis determined that the pressure of the reservoir water reactivated an old landslide area which sent 1.52 million tons of schist against the dam’s 271 thousand tons of concrete

Mulholland’s design also ignored the effects of uplift on gravity dams. In addition, the base of the reservoir was 20 feet thinner than the dimensions indicated in official drawings, which reduced the dam’s stability and made it more vulnerable to the effects of uplift.

Mulholland’s desire to finish projects on or under budget was at the expense of public safety. The concrete contained no reinforcing steel or contraction joints. Other design oversights include:

- No drainage galleries for inspection purposes.

- No cut-off walls or group curtains to control seepage and help prevent uplift.

- Few drainage wells were built into the dam.

- No drainage wells near the walls of the canyon.

Mulholland was also accused of using inadequate materials in the aqueduct. Recent research on the concrete used in the dam concluded that the concrete was substandard and would have started to deteriorate before the reservoir was even filled.

Repercussions were swift. The collapse had an immediate impact on the construction of the Hoover Dam. The project was delayed and then moved from Boulder Canyon to Black Canyon, where it sits today.

The St. Francis disaster also prompted the federal government to order safety inspections of all dams. These inspections revealed that one-third of America’s dams at the time needed repairs. Legislation was also passed to increase dam safety, and engineering geological input on dams became commonplace.

The St. Francis disaster was the catalyst for California to mandate professional registration for engineers in the following year. California’s Civil Engineers Registration bill sailed through the state legislature and became law on August 14, 1929.

Leave A Comment